The legacy of William the Bastard

Little seems to have changed since his time. Some two thirds of the British landmass remains in the hands of around 0.3% of the population that includes the Crown, various aristocrats and the Church of England. The social hierarchy is alive and well. And the psyche of the British masses remains deeply marinated in class consciousness, social distinctions and instinctive deference.

LONDON – APRIL 29: In this handout photo, issued by Clarence House, the bride and groom Prince William, Duke of Cambridge and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge pose for an official photo with (clockwise from bottom right) The Hon. Margarita Armstrong-Jones, Miss Eliza Lopes, Miss Grace van Cutsem, Lady Louise Windsor, Master Tom Pettifer, Master William Lowther-Pinkerton, in the throne room at Buckingham Palace on April 29, 2011in London, England. The marriage of Prince William and Catherine Middleton was led by the Archbishop of Canterbury and was attended by 1900 guests, including foreign Royal family members and heads of state. Thousands of well-wishers from around the world have also flocked to London to witness the spectacle and pageantry of the Royal Wedding.(Photo by Hugo Burnand/Clarence House – WPA Pool/Getty Images)

As a spectacle of pomp and circumstance the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton must surely have fulfilled every TV mogul’s wildest dreams. Hollywood could never compete. The setting was Westminster Abbey, founded by King Edward the Confessor in 1045 and the traditional place of coronation and burial for royalty down the ages. It is a potent and reassuring symbol of the monarchy’s quasi-religious resonance among the masses. The wedding guests were delivered in a cavalcade of Bentleys and elegant carriages, with minibuses for the lesser ranks, precision timing, no hint of confusion.

The bridegroom was a Prince of the realm, second in line to the throne and has a demotic job in the military. The bride, not of royal blood, would have given the followers of Helen of Troy reason to think twice although she had the advantage of modern make-up and dress design. And camera angles also for the world at large. Trumpeters and military salutes punctuated the proceedings at appropriate intervals while high fashion, scarlet and brocade, medal- bedecked chests shed an aura of gentility even on the politicians present.

This was pageantry at its best and most effective. Indeed one TV commentator is said to have used that very word over 80 times in one hour as though conferring a dusting of magic on the proceedings. And perhaps he was right, wittingly or unwittingly, for the word has roots in the ancient mystique of Europe’s ruling classes for whom visual impact was crucial in flaunting status and compelling respect.

It still is although it has gone public these days, watered down by the impact of advertising and the visual media. Maybe these inconvenient modern competitors were also at the back of a collective ruling mind which saw the wedding of these two young people as a timely reminder to Her Majesty’s subjects of the Crown’s totemic position at the heart of England, a common focal point of dreams and myths, legends and realities, the whole combined in a massive living symbol of ancient and unquestionable authority projected into an uncertain future by 21st century technology. This might explain the otherwise eccentric decision to have some WW II vintage warplanes fly over the festivities, a neat echo of a recently popular film that lauded the wartime monarchy’s role.

It is likely that amid the weight of history, wishful thinking and spiritual mist that enveloped the Abbey that day few persons, if any, remembered the man who almost one thousand years ago single-handedly built the grand stage on which the monarchy still performs its role. William, Duke of Normandy, born Falaise about 1028, invaded England 1066 and was crowned King of that country in Westminster Abbey at Christmas that year. He became William the Conqueror to history and to his contemporaries but previous to his adventures in England he was more modestly known in Normandy as William the Bastard because of his illegitimate birth to the daughter of a tanner in Falaise.

William had the predatory instincts of his Viking ancestors but made sure he had the blessing of Pope Alexander II before he set out to seize the crown of England. And the Pope gave him own special piece of pageantry for the expedition in the form of a consecrated banner. But William was not the sort of man a TV commentator could easily have painted into the distilled version of the glorious past on display at the Abbey. His historical image is not the stuff of comfortable middle-class escapism nor indeed does it offer much leverage to those in the small off-shore island who see themselves as somehow separate from and superior to their mainland neighbours. However it’s safe to assume that some of the wedding guests would have fully approved of his particular business methods.

William dealt in shock and awe, backed with brutality and death and was an ethnic cleanser and land grabber on a vast scale. Pageantry came second by some way; the mailed fist of the Norman knight was a far more effective form of authority. And his unfettered use of force and destruction laid the foundation for long lasting royal power, a heavily class- structured society and centralised government that still to this day permeate England from top to bottom.

Within some four years of his arrival in England William he had more or less eliminated the native Saxon aristocracy and stripped away their lands. By 1086 what was left of the indigenous nobility controlled around a mere 8% of its original property; the rest had been handed over to William’s own Norman French nobility. Two only of some 4000 Saxon lords survived and the former separate earldoms, distinct regions as in Germany, were brought under rigorous central control. William also knew exactly what he owned and its productive capacity since by 1086 the whole country had been inspected and reported in the Domesday Book, a notable advance in intrusive government and very useful tool for the extraction of taxes.

Hi s regime was repression in the widest sense for the various Anglo-Saxon tribes, now with subject race status, were corralled within an efficient (by the standards of the times) system of rule totally controlled from Church to countryside by a foreign military led hierarchy that spoke a different language, Norman French. London was the focal point of this power not because it was necessarily the best location from which to administer on behalf of the people; more because it was a conveniently located and easily defended stronghold and the Tower of London was built to reinforce the point.

The British monarchy and aristocracy have no real constitutional power these days although unelected nobles and bishops still linger in the House of Lords. Over the centuries those at the top from the monarch down were obliged, often reluctantly, to drip-feed the population that melange of rights, powers and liberties that now serve as the British version of democracy. Nevertheless much of the Conqueror’s legacy lives on in the 21st century its tough threads conspicuous in the warp and woof of English life.

The pattern of landownership seems to have changed little and some two thirds of the British landmass remains in the hands of around 0.3% of the population that includes the Crown, various aristocrats and the Church of England. No land tax is paid on this while land use bodies such as the Environment Agency appear to have only a tenuous public connection. And the social hierarchy born of the original Norman French aristocracy, rooted in the land, matured in the feudal system and swollen thereafter is alive and well. The sovereign’s family sits at the top of an extensive nexus of old nobility, titled individuals, patronage and hangers-on that is deeply embedded in society. The psyche of the British masses remains deeply marinated in class consciousness, social distinctions and instinctive deference. Not surprisingly it was felt necessary to grant Catherine Middleton, a commoner, a coat-of-arms, upon her marriage in order to show her social status.

Perhaps in the House of Lords one can see subconscious need to retain another layer of neo-feudal hierarchy as a bulwark against incoming tides of popular presumption. The House which is the upper house in Parliament is home to more than 700 unelected members mostly political cronies of various governments whom the Queen has plucked from the plebeian depths of plain Mr/Mrs/Ms and transformed into Lords and Ladies with all the necessary trappings and appurtenances to underline this.

And a very colourful spectacle they are when in full dress. It is as though wisdom and integrity are not enough and it is necessary to invoke ingrained historical conditioning reinforced by pageantry to overawe the common people. No mailed fist here but plenty of social clout backed by the royal imprimatur; the Conqueror would have understood.

Equality and the masses are dangerous concepts in the hands of political orators, just as dangerous as the notion of regional autonomy was to William in the 11th century. They may to this day unsettle the collective subconscious of England’s ruling classes who are still London-centric and for whom the monarchy is a support and fount of constitutional power. The Queen and her family are required to be apolitical but the British government is still the Queen’s government and its policies are still declared to British subjects (subjects, not citizens) in the Queen’s speech in the House of Commons. A population that became too obsessed with raw political debate might well wonder en masse whether a such a conspicuous and unelected Head of State was offensive to the principle of democracy. Or maybe even an obstacle to the idea that mankind’s future should be based on equal social respect for personal achievement and contribution. Once launched there is no saying where such a debate might end especially given the nature of Britain’s very divisive political culture, great gap between rich and poor (both echoes of the Norman land grab) and growing democratic deficit.

How much safer in the interests of stability to deflect any mass thinking about these things and keep the sovereign and her family right in the centre of British life as an anchor to which all can safely attach themselves in some way. An approach not without its dangers since there is no guarantee that all the royal dramatis personae will be 24 carat gold. But it has worked well in the case of the present Queen who has performed her duties tirelessly and diligently for over 50 years. And the status quo allows Britain’s tribalised political parties to carry on fighting each other, solving crises and creating crises, governing and misgoverning, running up huge debts, embarking on dubious wars safe in the knowledge that the centre will be held firmly together by the monarchy as it has been, despite the odd lapsus, since William the Conqueror arrived. And a well-choreographed royal wedding is the perfect distraction from an economy wrecked by political mismanagement. Indeed one scribe in a leading UK daily paper went so far as to write of ‘the broad sunlit uplands’ which the wedding would usher in for the country.

For the observer of European civilisation there is cause to wonder how it is that man has so enveloped himself in idols, symbols, the myths of history, religious rites, total trivia like social status and royal bridal dresses that he appears to be an organism adrift, mesmerised and confused by TV images and media drivel no longer able to see anything for himself. It is sad to reflect that getting rid of idols is one thing but changing human nature so that they are not needed is another thing altogether. And let us not forget that a fallen idol leaves a gap, a god that has lost its joss will soon be replaced by another with different priests and votaries steeped in the ways of hierarchical power and mass manipulation. Thus the comedie humaine continues.

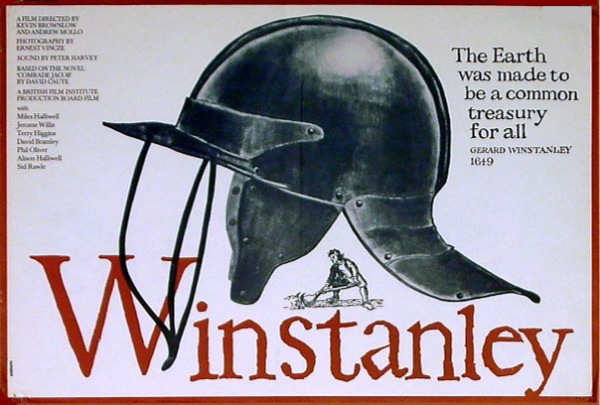

Charles the First, beheaded on January 30th, 1649

Not much remains of William the Conqueror himself now, just the odd bone and dust. His grave at Abbaye-aux-Hommes in Caen was defiled twice, in the French Wars of Religion when his bones were scattered across Caen and again in the Revolution. However, if the soul of this transplanted Norseman goes marching on it will have reason to be well content. The 68 metres of embroidered cloth known as the Bayeux Tapestry tell the whole world of his conquest of England . The Queen remains the largest landowner in the UK, fount of patronage and a contitutional influence behind scenes. The British military is still Her Majesty’s Armed Forces, her head appears on all her realm’s currency and stamps and she is still Duke of Normandy although her dukedom has shrunk to the Channel Isles. And in the fullness of time her grandson should become King William V with a similar imprint on British society and in the Channel Islands they will still drink a toast to ‘Le Roi, notre Duc’.

Indeed he cast a giant shadow, that bastard son of Falaise, from 11th century Normandy right across cyberspace to the whole 21st world by way of Westminster Abbey where he started it all.

Leo Colbert

Leave a Reply