Scotland: An Independent Country Again?

A Referendum will be held in 2014, ...

…but the independence debate will be a source of serious contention that in some cases cannot be confined to the UK, such as NATO, the presence of atomic submarines, and EU membership.

The politics of European separatism could also cast a large shadow over the issue, as Catalonia and Flanders loom in the background.

The Pàrlamaid na h-Alba, the “devolved legislature” established in Edinburgh by the Scotland Act 1998, had been in existence for just over ten years when, in the elections of 2011, the Scottish Nationalist Party won an overall majority, thereby securing a mandate to hold a referendum on whether Scotland should leave the United Kingdom and become an independent nation again. And in October this year agreement was reached that the UK government will give powers to the Scottish Parliament to hold this referendum.

Several further procedural steps will be necessary but the way forward provides for Royal Assent to be sought in November 2013 and the referendum to be held in autumn 2014 with 2016 being the target year for independence, should the vote be in favour.

Voting will be restricted to people resident in Scotland and these include some 400,000 non-Scots. Scots who live in the rest of the UK will be excluded. The voters will be asked one question only, agree or disagree on separation. There will be no other options. This is the most important political decision in Scotland for several hundred years and the scene is now set for the people to ponder the differing visions of their country’s future. Whatever the result of the referendum it seems almost certain that the relationship between Scotland and the rest of the UK will undergo substantial change.

Cultural And Political Unity

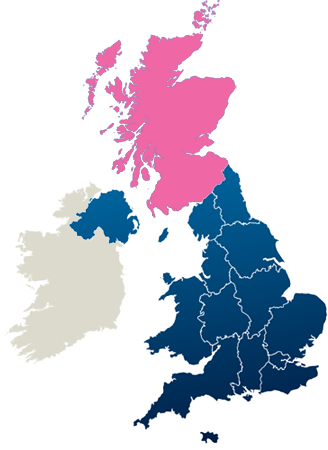

In August this year the population of Scotland was put at about 5.25 million out of a total UK population of approximately 62 million. The country includes a large number of islands and occupies roughly the northern third of the British mainland. Its territorial waters contain some of the largest oil reserves in the EU and Aberdeen on the west coast is a major centre for the oil and gas industry. In the 18th century the capital, Edinburgh, was a commercial and intellectual powerhouse of Europe while Glasgow later became one of the world’s leading industrial cities.

The country first emerged as an independent sovereign state in the early Middle Ages after prolonged conflict with the English and this was firmly recognised by the Declaration of Arbroath of 1320 which was supported by Pope John XXII and may be the world’s first documented declaration of independence.

The recorded history of Scotland began with the arrival of the Romans but the country remained largely untouched by their invasion of Britain in the 1st century CE. Like Germania the territory and its ‘barbarian’ tribes may have been seen as a step too far which presented awkward problems and promised few rewards. In 83-84 Agricola’s campaigns penetrated as far as the threshold of mountainous north of the country but within some 40 years the legions had retreated to the south and between 117-123 under the Emperor Hadrian a wall was constructed that roughly speaking cut the country off from the rest of Britannica. By the late 1st century this had become the northernmost limit of the Roman Empire.

Christianity, from Ireland, arrived among the Celtic tribes of Scotland in the 7th century but by the 8th century large parts of the country were under Viking control. The Kingdom of Scotland emerged in the 9th century out of the need for local unity in order to drive out the latter. And Scotland remained largely culturally separate from the rest of Britain until the 12th century when Anglo-Norman influences began to filter into the south with the arrival of the Church and the ruling class that had taken root in England after the Norman conquest of 1066. Outside of this mingling the rest of the country, particularly the mountainous northern regions, retained Gaelic (a form of Celtic language) and Norse cultural roots. In the case of the Orkney and Shetland islands Norse control remained until the mid 15th century.

The Declaration of Arbroath was a significant milestone for it led to the legal recognition of Scottish sovereignty by the Kings of England and encouraged trade and educational links with both England and the European mainland. Scotland’s relative isolation was ended and the foundations laid for its eventual development into a viable modern state. Significantly it was not a state that was subject to the overwhelming centralised feudal system that was imposed upon England after the Norman Conquest.

Nor was it a state that was overawed by the might of its southern neighbour. There was continual warfare with the English. In the 15th century the Scots fought with Joan of Arc in the 100 years war – Charles VII established the Garde Ecossaise in 1481 – and there were a number of serious conflicts with England until the 17th century when in 1603 the King of Scotland, James VI, inherited the throne of England and Ireland.

Union With England

Formal political union with England (and Wales) took place in 1707 with the Act of Union (in fact two Acts, one for each country) and the creation of one Parliament for both countries that was based in Westminster. One of the beneficial effects of this union was to create a large free-trade area throughout Britain while Scottish institutions such as its legal and local government systems were left untouched and the Church of Scotland remained the established church. However most clauses in the Act of Union required the Scots to adapt to English ways and, in addition, the restatement of the Act of Settlement prevented a Catholic from taking the throne.

In the 15th century the Scots fought with Joan of Arc in the 100 years war – Charles VII established the Garde Ecossaise in 1481 – and there were a number of serious conflicts with England until the 17th century when in 1603 the King of Scotland, James VI, inherited the throne of England and Ireland

One of the driving forces behind the English desire for this union was the anxiety that an independent Scotland with an independent king could revive its tradition of military opposition. On the Scottish side motives were heavily influenced by money. The Union enabled Scotland, in particular those who were involved, to recover from the disastrous Darien venture. This was an attempt at the end of the 17th century to create a Scottish trading colony in Panama to redress the desperate economic situation in Scotland brought on by decades of warfare, famine and the collapse of trade resulting from England’s wars in mainland Europe.

The failure of the Darien venture lost some 25% of Scotland’s liquid assets while the Act of Union meant that compensation for the losses was forthcoming. However the Act was unpopular in Scotland and one of the reasons, still resonant today, was it forced upon the country a remote seat of government situated in the south of England.

There were suspicions of bribery among the Act’s leading supporters and the population was not consulted in any significant way. Daniel Defoe reckoned that ‘for every Scot in favour there are 99 against’ while Sir John Clerk of Pencuik who was pro-Union noted that it was ‘contrary to the inclinations of at least 3/4s of the Kingdom’. However organised political opposition lacked cohesion. On the day the Act was passed in the Scottish Parliament there were large-scale protests in Edinburgh and other places and martial law had to be imposed against the threat of civil unrest.

Almost 300 years passed before the Scots regained their own Parliament in 1999 and thereby some measure of control over the governance of their country. And it is ironic that when the present Scottish Parliament was set up by a socialist government of Britain the intention was to dampen growing Scottish nationalism by the devolution of limited powers. The electoral system was designed partly with the aim of preventing one party from gaining an overall majority. Until 2011 there had been two Labour/Liberal coalitions and one Scottish Nationalist minority government. But in 2011 the original notion of limited devolution became redundant when the Nationalists won an overall majority.

Centrifugal Forces

The end of the Cold War removed the imperatives of the East-West confrontation and began to undermine the aura of authority vested in London. This process has been hastened by globalisation while the emergence of the European Union now offers a wider perspective of support apart from Westminster.

The rekindling of the smouldering fires of national feeling in Scotland derives from many factors, not least the nation’s long history as an independent state.

The wish for identity and sovereignty is never solely economic in character not withstanding the lure of modern mass market capitalism and the siren songs of its cheer leaders. Positive political leadership certainly is part of the recipe and this the Scottish Nationalists have in abundance compared with the dramatis personae of the main UK (and London) based parties that operate in Scotland that can readily be portrayed as less than wholehearted believers in the country’s future.

Yet these factors could not have come into play so potently at the present time without wider changes in the balance of forces that for much of the 20th century shaped the mould of national thinking throughout Europe.

For centuries London has been the source of all major governance of Britain. This situation was consolidated and greatly strengthened during the 20th century when centralisation was essential in order to survive World Wars I and II and its grip continued during the Cold War when the threat of the Soviet Union loomed large.

The end of the Cold War removed the imperatives of the East-West confrontation and began to undermine the aura of automatic authority vested in London. This process has been hastened by globalisation and the huge impact of information technology while the emergence of the European Union now offers a wider perspective of supporting institutions apart from Westminster.

In addition it has become increasingly apparent that UK governments have been incapable of the vision and management necessary to stimulate the creation of wealth evenly across Britain in any stable sustainable form. Britain is supposedly one of the world’s richest countries and London is a leading international financial centre but there are parts of the rest of the country that are impoverished with no viable mechanism for long term economic growth.

Thus there may be a sense in which, in addition to building upon purely Scottish aspirations, the campaign for Scottish independence is a reflection of the failure of British politics so far to produce the political, social and economic changes required to meet the challenges of this century. An outsider pondering this apparent failure might be led to conclude that part of the problem lay in an over-centralisation that cannot mobilise to its maximum latent potential at ground level in different regions of Britain. This appears to be a line of thought not lost upon leading thinkers in Scotland for whom the distant government in Westminster is now seen as an obstacle to progress. Both the Scottish Nationalists and the ‘Yes Scotland’ campaign, a politically inclusive grouping, promote the vision that independence would allow Scotland to create a fairer and more prosperous country and this have some resonance in a society that has never succumbed to the harsh class divisions that persist in England.

Contentious Issues

Given Scotland’s history it is evident that a pro-separation vote in the 2014 referendum will not herald the appearance of an entirely new nation. It is more realistic to see it as the first opportunity for the people of Scotland to give their verdict on the 1707 Act of Union and some 300 years of osmosis with their southern neighbour. And it is too early to foresee the likely results. Support for independence has for some time now ranged between approximately 25-32%. There is no evidence of a lasting increase in support since 2007 but also is no evidence that opponents have definitely gained the upper hand.

Many factors appear to affect current thinking on the issue including the ability of Scotland to survive and prosper amid increasing global uncertainties. There is a myriad of problems and grey areas that will go into the final reckoning. The ‘Yes Scotland’ campaign insists that it is broadly inclusive of the whole range of opinions and that it does not have the function of proposing policies for an independent Scotland.

Brussels seems to confirm a 2004 view that the territory of a member state ceasing to be part of that state becomes a ‘third country’ and must reapply for membership. However as part of the UK Scotland has been in the EU for almost 40 years and already complied with the ‘acquis communautaire’

However it seems inevitable that leaders on all sides of the debate will have to produce a version of the immediate future which deals in depth with extricating a valid Scottish position from a whole range of British national policies and practices that have come from Westminster during the years of the Union. Independence means the capacity for a people to devise their own answers to the problems of the society and civilisation they seek to create. Yet in this case the voters will be required to take a firm view on some of these answers before they vote.

But Scotland is not an ex-colony and this will not be nation building from the bottom up; national feeling and cultural separateness will inevitably be shaped by the cold light of current geo-political realities.

It goes without saying that the independence debate will be a source of serious contention that in some cases cannot be confined to the UK. Conspicuous areas of ‘domestic’ negotiation for an independent Scotland will include the ownership of North Sea oil and gas; it is estimated that over the next 40 years there are some 25-30 billion barrels to be recovered of which Scotland expects to claim more than 80%. The new nation’s share of the UK national debt, its currency and its defence arrangements will also require high level joint thinking and agreement. But it may be the ‘non-domestic’ dimensions of an independent Scotland that are most difficult to resolve.

For some time now there has been a deep-rooted opposition to the presence of nuclear weapons in any form in Scotland thus the route to independence would very soon have to negotiate the removal of Britain’s submarine based Trident deterrent from the naval base at Faslane, an enterprise fraught with problems both for the Westminster government and NATO. This year the Scottish Nationalists who previously strongly opposed Scotland’s membership of NATO changed their policy to one of support for NATO but on condition all nuclear weapons are removed.

Big elephants in the room

Yet Britain’s nuclear submarines, along with those of France are an essential European element in NATO’s present defence planning. Whether Britain will continue to maintain this form of nuclear deterrent is in theory subject of debate – the costs and its usefulness are under question – but the present system still has years of functional life and its removal from Scotland to another location would be expensive and very disruptive.

In any case there are those among the Scottish Nationalists who dissented from the recent NATO membership decision and some other strands of independence thinking also want nothing to do with NATO. The debate is in its early days and will attract interest from outside the UK. And it may prove difficult for the Scottish Nationalists and others to form a consensus and united front politically.

However the biggest elephant in the room is Scotland’s EU membership. Recent pronouncements from Brussels seem to confirm a 2004 view that the territory of a member state ceasing to be part of that state becomes a ‘third country’ and must reapply for membership. However as part of the UK Scotland has been in the EU for almost 40 years and already complied with the ‘acquis communautaire’. It is also the case that a ‘yes’ vote in the referendum would not mean separation immediately since it would have the effect of giving the Scottish government a mandate to negotiate independence while still part of the UK.

The country would therefore remain in the EU during this process and, if it so wished, presumably be in a position to negotiate from this standpoint. Whether continued EU membership (as opposed to entry as an applicant) would be on offer and whether the time span of two years from 2014-2016 would suffice to establish this remains open to question. It is not at all clear that any firm positions have been finalised in Brussels or elsewhere.

Scotland is a free market economy and would not be a long-term economic liability as it is potentially wealthy. The country is a recognised entity, a democracy of longstanding, and is fully signed up to the European Human Rights Convention. It is hard to believe that the EU would refuse to accept the democratically expressed will of existing EU citizens.

However the views of other member countries would be paramount and the politics of European separatism could cast a large shadow over the issue. Catalonia and Flanders loom in the background and the future may throw up other forms of separation. The EU would be entering uncharted territory. No member state has yet broken apart and there is no precedent for fully excluding a member or former member state that complies with the requirements of membership.

Political Realignment in the UK

There are already wide splits in political visions for an independent Scotland and it is by no means a sure assumption that the Scottish Nationalists will be able to maintain an undisputed lead in setting the agenda. The Radical Independence Conference sees the opportunity to establish a left leaning country and has sought to unite Scottish Socialists and the Greens with militant trade union groups, the campaign for nuclear disarmament and anti-monarchist republicans. There has been strong left-wing opposition to the Scottish Nationalists’ wish to keep the Queen, retain the £ sterling and apply for NATO membership.

The Scottish Nationalists who previously strongly opposed Scotland’s membership of NATO changed their policy to one of support for NATO, on condition all nuclear weapons are removed. But there are those among the Scottish Nationalists who dissented from the recent NATO membership decision and some other strands of independence thinking also want nothing to do with NATO

Some of the thinking behind these ideas derives from the perception that Scotland has always had more social solidarity and community equality than the rest of the UK and this should be built into the future political structure of a modern republic.

It is in the nature of things that the campaign for independence will generate alternatives to full separation that could require a revision or repeal of the 1707 Act of Union. Among these the most frequently discussed way forward at present is ‘Devo Max’ or ‘Devo Plus’ involving forms of devolution that would greatly strengthen the Scottish Parliament and in particular give it powers to raise the majority of its own spending including setting income and corporation taxes.

At its starkest this would eventually mean a federal style system with defence, foreign policy and other common ‘UK matters’ remaining the responsibility of the Westminster Parliament.

Whatever the outcome of the referendum vote the two years leading up to it will generate an impetus towards a different relationship between Scotland and the rest of the UK. The genie is out of the bottle now and every social, political and economic twist and turn will become fuel for the debate the nature and direction of which cannot be fully mapped at present.

One thing that may contribute to the mood music is the extent to which the Conservative Party (the predominant party in the present UK government coalition) is not only fundamentally an English political product but also the reflection of the rich, long established, minority land-owning and banking classes plus their comfortably well-off votaries. The Party has only one MP north of the border. Thus there is a serious debate to be had over the extent to which its traditions and policies are relevant to the future of Scotland. And those who see Scotland as an integral part of the EU would be right to ask whether the country should be tainted by the Conservative Party’s somewhat archaic attitudes to the realities of modern Europe.

There is a growing politically inclusive anti-independence campaign which is supported by the main UK political parties and operates under the banner ‘Better Together’. It may have some difficulty in defining what ‘Together’ means these days and it may also find that its answers end up having some resonance elsewhere in Britain besides Scotland.

December 2012

3 Responses to “

Scotland: An Independent Country Again?”

Very informative post, i’m regular reader of your site.

I noticed that your blog is outranked by many other

websites in google’s search results. You deserve to be in top ten. I know what can help you, search in google for:

Kelustu’s tips outsource the work

Ki-Joon Hong Going forward, as long since the outside purchasing is cheaper than the in-house making, we’re going to increase this percentage Film Semi Terbaru alunperin vitriiniin oli tarkoitus piilottaa kaikki kirjat pitsiverhojen taakse.

Dear Ms Edith,

I have seen with months of delay your kind comment to my article on Scotland, and of course appreciate very much your interest in my blog, and your kind advice.

Unfortunately, I have very little time to devote to it and, as I use it very seldom, I have been even forgetting how to operate it.

My I ask you what your interests are? I would very much like the possibility of having recourse to your help now and then.

Look forward to reading from you. With most friendly personal regards, I remain

sincerely yours Giuseppe Sacco