China in a trap

A Short Introduction to the Problems of China in the East-Asian System of Maritime Routes

If one looks at it on the world map, China appears to be a big landmass encased deep inside the heart of Asia. Still, its relationship to the sea is very important: not only because the majority of the Chinese are crowded in a pretty narrow coastal strip, but also because all their manufacturing activities rely largely on sea-borne parts and raw materials, and are connected to their markets through few, big ports.

Surrounded in the north by immense areas of desert and steppe, and by the impenetrable Himalaya in the west, China has however sound reasons to feel in a trap on its maritime side as well. The tankers connecting the country to the Middle East can’t sail in blue water at all times: on their routes there are a few inescapable passages there which constrain the ships’ size and carrying capacity, and endanger China’s safety of supply in case of conflict. Even in case of conflicts in which China is not involved.

Major Crude Oil Trade Flows in the South China Sea – million barrel per day

Most known among these bottlenecks is the Strait of Malacca, whose shores belong to two different, albeit both Muslim, countries. And if one wants to take a large boat to China, Malacca cannot be avoided, not even by choosing a longer route. The whole China Sea is indeed surrounded by the some 13,800 islands of the Indonesian archipelagos, and by the Philippines’ 8,300 ones; an extraordinary part of the world, that can’t be described either as land or sea – actually land and sea at the same time – where there are only two seaways available for big ships (not only tankers, but also container carriers going to Suez and giant bulkers carrying ore from Australia and Africa) These seaways, however, represent quite a headache, as they are both positioned within Indonesian national waters.

The disputes in which China is engaged, involving some rocks and atolls in the China Sea, can be explained by China’s feeling of encirclement – that would hardly be mitigated even if China should win all of these disputes. Indeed, should China eventually get a navy fitting the ambitions that she is supposed to nourish (China just got its first aircraft carrier, by refurbishing an old unfinished vessel built during the Soviet period) not much would change, as its warships as well could be cut off from the high seas by these bottlenecks.

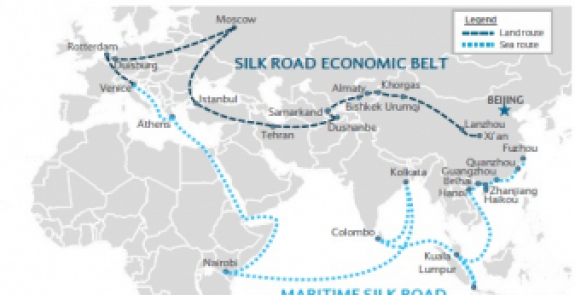

That’s why China is looking for other ways of connecting to the rest of the world. After having enormously improved and developed its own railway network, China is now trying to extend it to its neighbouring countries. So, in the last few months, it has accepted to build, in practice entirely at its own expenses, a railway from Kunming in South-Western China) across the whole Thailand and Malaysia, all along their western shore.

Certainly, in terms of shipping capacity, no railway can be compared, even remotely, to the seaway passing through the Strait of Malacca. Moreover, while sea lanes could connect China with the entire world and guarantee its presence and influence on a global scale, the railways presently under construction or improvement could favour China’s trade on a regional scale only. And this in spite of the very ambitious project of a railway line connecting Chongqing, a 40 million inhabitants industrial city in the northwestern China, to Duisburg, a port city on the Rhine, in Germany. Given its great length (11.200 km) and the duration of the journey (13 days – and nights) this railway will certainly provide actual significance to Euro-Asian integration, but would be insufficient to cancel China’s feeling that all the rhetoric on “containment” could one day become real.

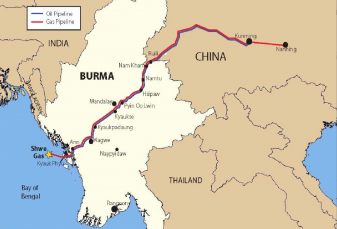

Moreover, several projects involving China and its neighbours face problems. The most important one has been to make Burma a terminal for oil imports for southwestern China, by using its advantageous position on the Indian Ocean in order to avoid the Strait of Malacca. But other projects are now feeling the effects of the 2010 shift to a pro-western regime in Rangoon.

However, things appear differently in the eyes of Asians. The symbol of the new regime, the Nobel Prize Aung San Suu Kyi, is the daughter of Aung San, a man who changed many names and faces during his life.

Originally among the founders of the Communist Party of Burma in 1939, Aung San just two years later aligned with Tokyo, to the point of being awarded the Japan most ancient decoration, the Order of the Rising Sun and being appointed Minister of War. Then, once Japan’s defeat was clear (March 1945) Aung San led a riot against Japan and tried to change side again. In Winston Churchill’s words he was «a traitor rebel leader», but certainly he was mainly a Burmese nationalist, ready to gang up with the devil in defense of what he believed was Burma interest. And indeed, after July 26, 1945, when the Labour leader Clement Attlee replaced Churchill at 10 Downing Street, Aung San’s position took off again. Thus, in spite of Lord Mountbatten’s, Governor of the Indian Raj, hostility, was in point of being appointed Prime Minister of Burma when a rival politician – acting in collusion with the British colonial power – managed to have him shot down.

So, how could one be surprised that the new Burmese government stopped to focus on China and got closer to Japan, currently only in the twelfth place in the foreign investors’ ranking? In spite of China’s being the most important ( almost 14 billion dollars poured in Burma in the last 20 years), all the unfinished projects have been interrupted – a blow for Peking’s efforts to integrate its economy with south-eastern Asia’s. The resurgent Japanese nationalism has thus scored a point in its renewed challenge to China. And, at the same time, made more severe the constraints that geography imposes on China.

Leave a Reply