A Farewell to Italy:

Demography and Immigration

“Es wurden Arbeitskräfte gerufen, aber es kamen Menschen.”

Max Frisch

(‘A workforce was called in, but instead it was people who came.’)

There was, in the 1960s, much talk of ‘revolution’, in Italy no less than in France, Germany and the US. All in all, seen with the benefit of hindsight, most of it can be considered more a case of collective infantilism that an explosion of extremism. Still, in Italy the turmoil dragged on from 1968 until 1978, producing a wave of terrorism (some aspects of which remain still unexplained) and reaching its apex and conclusion with the Aldo Moro assassination.

In political terms, such a ‘revolution’ failed completely, but some of the consequences of that attempt are unexpectedly ravaging Italy in the new century. For something revolutionary did happen, and it took the form of a radical change in the behaviour – in particular in the sexual behaviour – of the subsequent generations, above all among the women of Italy. Although this gave rise to long-overdue advances in the professional and social equality of women which are now irrevocable, it also brought about a change in reproductive habits that – along with the invention of the ‘pill’ – has rapidly turned out to be incompatible with a satisfactory cycle of population renewal.

In fact, for the peninsula’s demography, the birth-rate peaked in the middle of 1960 and then went into uncontrolled decline, which appears bound to continue in the coming decades as well. Today, fertility is around 1.3 children per woman: a rate which is not compatible with the maintenance of a minimum balance between age groups and thus between the classes of the population that are of the age to work and create wealth, and those classes of an advanced age which need the support of society.

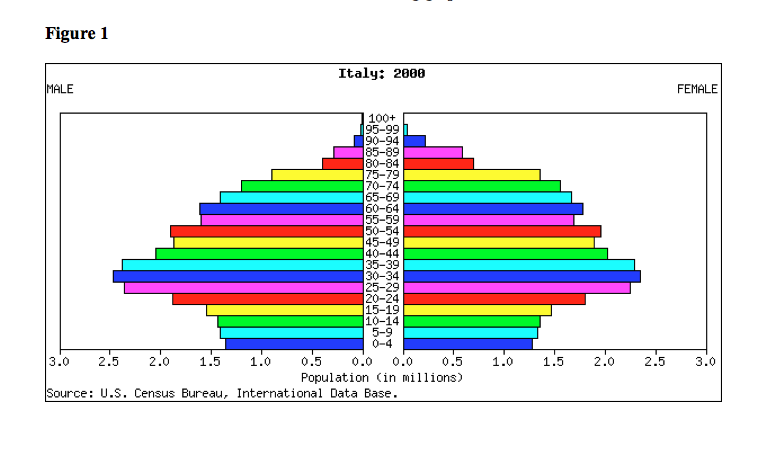

Italy has been one of the first developed countries in which the number of births and deaths have balanced each other, resulting in zero population growth. Consequently, since the 1970s, another phenomenon which is fully under way, that is, the progressive increase in length of life expectancy , has weakened natural dynamics still further. The results can be seen in the following graphs.

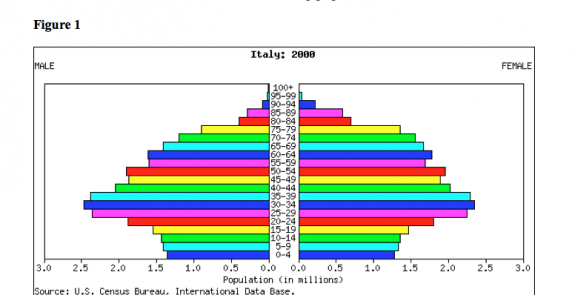

From Figure 1 it can be seen that in the year 2000 the adult sectors of the population in the Italian peninsula were greatly in the majority, compared with the younger sectors.

It is thus easy to understand why such a decrease in the birth-rate is the phenomenon that has characterized society since the second half of the fatal 1970s. Indeed, demographic decline has been so strong that the outline of this graph, usually called an ‘age pyramid’ no longer looks like a pyramid, but rather a rough rhomboid. Moreover, the future prospects seems even more negative.

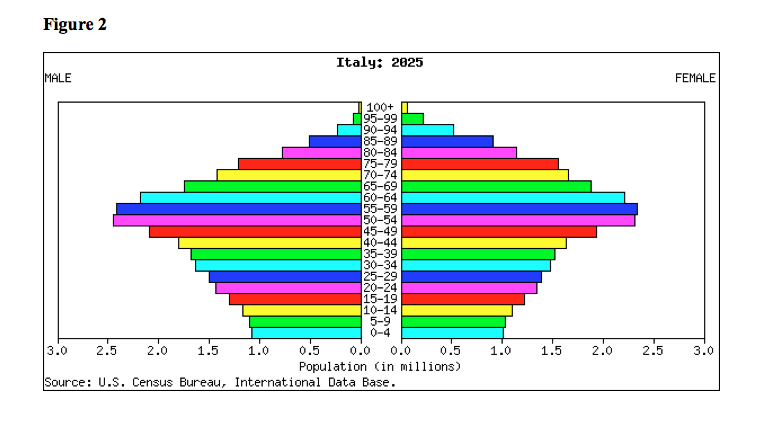

In Figure 2, which illustrates the forecasts for 2025, the base of the pyramid has now shrunk and appears to be an inherently unstable construction.

In addition to the many groups over 65 – the traditional age for retirement, and which, because they no longer generate earnings, are a burden upon the younger generations – there can also be seen the formation of a vast stratum of men and women over 85.

Above all should be noted the appearance of a category which for the first time has statistical significance: women who are over 100 years of age. As well as being unable to contribute in any way to the collective good, these people are as a rule not self-sufficient and need personal care and assistance.

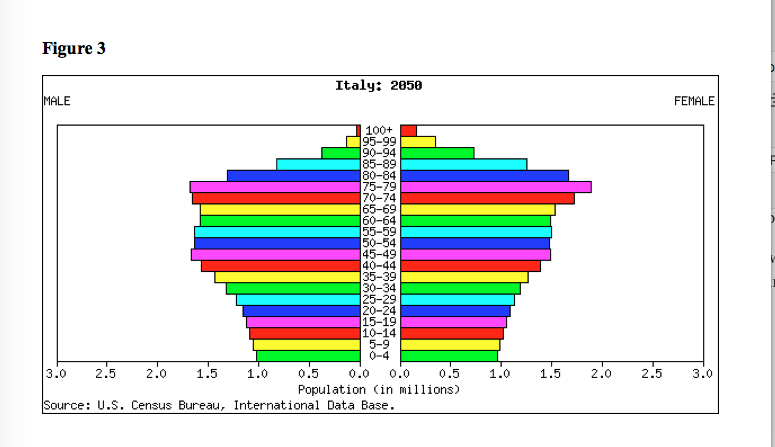

Projecting the picture further forward until 2050, in Figure 3, it then seems clear that Italy must expect a further decline in births and a growing increase in the number of people over 85. The situation promises to become completely unsustainable.

Looking at these three graphs in succession in order to obtain a dynamic picture, the impression is that the very plentiful post-war generations, the so-called ‘baby boom’ generations, have moved upwards through the whole demographic structure, like an embolism, until they have reached its head. What should be a pyramid has at this point taken on the form of a moneybox. But, on the contrary, the outline of Figure 3 effectively demonstrates that in the next few years there will not be enough resources to deal with the needs of broad sections of an extremely old population. In practice, this had already started to become evident in 2006, when the most numerous of all the generations alive, that born in 1946, reached 60 years of age.

A Rise in the Birth-Rate?

For two or three years there has frequently been talk in Italy of a rise in the birth rate. It is said that the Italians have been having more children for several years now. This is not entirely untrue. A certain change in outlook can be seen, namely in more educated and progressive women; and the female fertility rate went from 1.26 children per woman in 2003 to 1.33 in 2004. Even if still a long way from the 2.1 rate necessary to safeguard reproduction of the species, this is undeniably an encouraging sign.

However, it would be an illusion to take this slight rise as evidence of a reversal in the trend which might generate its own answer to the problem. This would be an even more serious delusion than the well-known one Napoleon I wished to spread around war-decimated France, that is, that the French would be capable, in one night, to fill the gaps left by his battles. Our delusion would indeed be more serious than the French emperor’s, because at the cusp of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the female population of France was very numerous and very young and (with a population of more or less half that of today) the number of births in France was double its present-day figure. In twenty-first-century Italy, instead, because of the overall ageing of the population, the percentage of potentially fertile women –those between 18 and 35 – has drastically reduced.

Thus, a possible resumption in the birth-rate would take place on a very narrow base. There would be a very few women to produce more children if in reality this were to happen. Even if fertility, as a pure working hypothesis, should reach Third World levels, the increase would take much longer than the decline has.

The unlikelihood of a possible resumption is made greater by the fact that the rhythm of demographic events in Italy has been greatly slowed down by the propensity of women – who are by now established in the working world – increasingly to delay the age of maternity, to the point where the span of one Italian generation is today double what it is, for example, in Colombia.

Finally, it is necessary to show clearly how the fact that in 2004, for the first time in many years, the number of births was not much lower than the number of deaths does not indicate any reversal of the trend. In 2004, there were not many more births than usual, but only far fewer deaths. And this abnormally low mortality resulted from the fact that the terrible heat wave in August 2003 had killed many old people who in normal climatic conditions would probably have lived some months longer and died in 2004 instead.

Towards Italy

Given that one ought not to count on a resumption in the birth-rate as a corrective to the demographic situation in Italy, or at least not expect anything of it in terms that might be significant enough to avoid a complete collapse of the socio-economic system, the alternative that is generally considered is immigration. But this raises other questions which are not easy to answer.

The flows of immigration to Italy from abroad have caused a very real upheaval in a quite short space of time. In the 1970s, Italian emigration to other countries dried up, and was replaced by a reverse population flow. Movement into the country – previously limited only to an economic and social élite – became a mass phenomenon.

In fact it was a very different form of immigration from the one observed before, when enriched English and German politicians and public intellectuals followed the fashion of buying sumptuously restored farmhouses amid the vineyards of Chianti, so they could play ‘gentleman farmer’. The phenomenon was so widespread in the SPD in Germany that there could be found there a parliamentary group ironically baptized ‘Toskana Fraktion’, just as the area where the London political elite likes to transfer its social life in the summer months has been branded ‘Chiantishire’.

In the last two decades of the twentieth century, immigration into Italy became a very different phenomenon, as it was above all derived from economic factors. And indeed its effects are to be seen in the economic field rather in Italy’s demography. In practice, it consisted of a spontaneous flow of labourers attracted by job possibilities in the peninsula’s economy and – as was to be expected – it ended up by filling those scarcities that existed in the workforce, but not the gaps in the population which resulted from Italy’s insufficient birth-rate. And as there was no sign of any policy aimed at attracting an inflow of men and women who might rescue Italy from demographic catastrophe, economic factors proved unable to trigger any substantial change in population trends.

Contrary to general belief, migrations are not a simple phenomenon made up of interconnected pots from which the flow tends to balance differences in demographic density or wealth. They are a complex sociological phenomenon where cultural and political factors come into play. The immigrant is neither a thief who seeks to steal jobs from Europeans, as is believed by the most fearful and extremist of the latter, nor – as portrayed in the gutter press – is the immigrant an invader who wants to replay in the reverse the past phenomenon of European colonization of the Third World.

In fact, from an economic point of view, the immigrant today no longer belongs to the most destitute sections of the Third World population. Rather, he or she is someone who has already absorbed a certain number of western skills, and is motivated by their own aspiration to a better economic situation, and by the aspiration of their enlarged family, who have contributed to finding the necessary resources to pay for the immigrant’s passage. Furthermore, from the political and cultural perspective, the immigrant is a person who has to some extent rejected the ideals of the society in which they were born. This attitude is not to be confused with that of the second and third generation, that is, of the immigrant’s children and grandchildren who, if they grow up in a western society, and face all the difficulties related to the social status of their parents, end up idealizing their culture of origin, and risk becoming suburban thugs or members of some extreme Islamist group.

The immigrant himself, the man – and, more and more frequently, the woman – who takes the decision to abandon their archaic society in order to come and live in a very different and much more secular one, is a semi-westernized person, already seduced by one of the myths of the ‘globalized’ world, the myth according to which cultural differences have been greatly reduced or are even in the process of disappearing altogether, and according to which national identities have been replaced by the homogenized tastes of people who are no longer citizens (or subjects) of various countries, but simply ‘global’ consumers. In short, the phenomenon of modern migration is very different from the barbarian invasions of the past, or the English colonization of North America, which resulted in the acquisition of a territory being taken away from a demographically weak population by one which was more numerous and prolific.

Immigration as a Corrective ?

Thus immigration into Italy, as a spontaneous, market-driven phenomenon, seems unable to meet the demographic needs of the country. For this to happen it would be necessary for the government to have a policy on population; but this does not exist. The authorities limit their activity in this field – crucial as it clearly is – to assessing shortages (in quality as in quantity) in the labour market, in order to set annual immigration quotas – quotas which are always greatly exceeded anyway.

The most serious workforce shortages – as becomes evident year after year – are in a quite specific sector of the labour market: those jobs that Italians refuse to do. This is clearly indicated by the fact that about 2.7 million immigrants of working age find work in Italy while almost 1.5 million Italians who are ‘in the prime of life’ are officially unemployed.

There are, however, some more indisputable facts which must be taken into account if one wishes to draw a more realistic picture. First, to any official figures for the Italian economy one must always add 15 per cent to cover the ‘black’ market. Secondly, the sectors in which ‘irregular workers’ are most frequently found are often made up of very labour-intensive activities. Finally, the number of Italians who have two or three jobs is far more than the number of the truly unemployed. One thus arrives at the conclusion that unemployment in Italy could be expressed by a negative number. Which is to say that – in spite of the weight of some ‘disaster zones’ such Naples, Palermo, or Calabria – the overall national level of unemployment is below zero. Within this framework, immigrants have as their function (and their aim) only that of taking up work that Italians refuse to do. Indeed, indispensable as they are, they cannot take the place of Italians in the economic domain, and even less so in the demographic one.

Until now the labour market’s need for immigrants has been quantitatively more important than the deficit in the population’s birth-rate. That is, in absolute terms, the positive balance in migration is greater than the negative balance in natural dynamics. The total population of Italy has continued to grow in the recent years because the immigrants who have come to work in the peninsula have been more numerous than the ‘unborn’ Italian children. It is possible that this will last for some more time, since the potential for influx is still considerable, as is evidenced by the constant pressure from the entrepreneurial sector for a relaxation of the bureaucratic restrictions on entry to the country. But there is no guarantee that immigration can continue to compensate for the decline in population. Indeed, the two phenomena simply coincide in time with one another, while remaining fundamentally different and only marginally related.

The Limits of Immigration

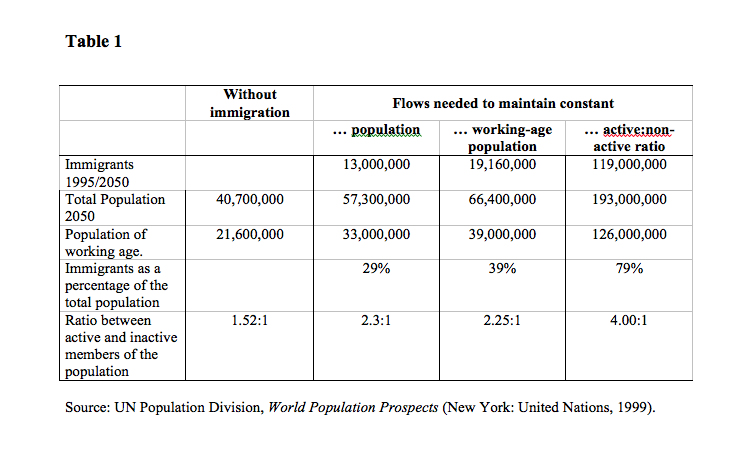

According to projections based upon UN data, any strategy aimed at having recourse to immigration in order to fill in the gaps left by the decline of Italian population could bring about a complete collapse of the situation, and, in reality, the end of Italy. Everything revolves around the level of quantitative relations between the non-productive age groups. It is indeed estimated that the ratio between the population of working-age people and the over-65s could increase from 3.94:1 in 1999 to 1.73:1 in 2049. In other words, while there are today about four people of working age for every person over 65, in 2049 this ratio will have been more than halved.[1] In order to compensate for the falling birth-rate, the population of Italy would in effect have to reach the levels indicated in the following table.

As can be seen, these forecasts involve extremely large flows. Merely to maintain the Italian population at the quantitative level equal to the last year of the twentieth century – and without paying heed to its internal composition, average age and the ratio between active and inactive members – a yearly influx of a total of 235,000 immigrants would be required for fifty years in succession.

When one thinks only of one year, this is not a huge figure. In the end, it corresponds more or less to the number of foreigners who have entered Italy annually over the last few years whether within the regulations or not.

However, if one looks at the internal composition of the Italian population, rather than at absolute numbers, and if the conditions which at present allow the welfare state to function are to be left unchanged – that is, a ratio between active and inactive members of approximately 4:1 – it would be necessary to have an influx of immigrants of around 2.2 million per year for almost half a century without interruption. And it would be necessary, of course, to create the number of jobs which meet the needs of this new component of the Italian population. By the year 2050, the population of Italy would amount to 190 million as opposed to the 60 million today. Of these 190 million, only about 40 million would be of Italian ‘stock’ while 150 million would be of immigrant origin. And about 100 million new jobs would have to be created because the active population should increase from about 20 million to 120 million approximately.

These data speak for themselves, and do not need much comment. They demonstrate clearly enough that in the present state of things, immigration is able to maintain the peninsula’s total population, looked at as crude data, at a little more than constant, but it cannot rectify its rapid and growing ageing. In fact, one should not overestimate the contribution that immigrants may be able to make to the birth-rate.

One should not count on female immigrants maintaining the characteristic birth-rates of their country of origin once they are settled in Italy. On the contrary, the example of the local population, and the conditions of life in the host country, cause them rapidly to adopt local customs in this respect. The fertility rate of foreign-born women is indeed around double that of Italian women, and slightly over that of foreign-born women in France, but still too low to compensate for the demographic decay of the country.

Such a substantially equivalent propensity to have children is apparently illogical, as foreign-born women in Italy have been exposed to Italian low-fertility culture for a rather short period, and are on the average younger than foreign-born women in France, where the great immigration waves have taken place around twenty years before migrations into Italy even began. But it can be explained with the fact that a great number of female immigrants to the Italian peninsula originate from eastern Europe, where fertility rates are very low. Moreover, a non-negligible share of Albanian and Romanian immigrant women are trapped before they leave the home country into rings that exploit them as prostitutes, while women from Muslim countries – more numerous in France than in Italy – tend to marry and have children.

It is clear that in reality an influx of immigrants such as that required by the UN forecast to maintain the 4:1 ratio between the active and inactive population has no chance of happening. Probably, long before the level of immigration reached the consistency necessary to bring the peninsula’s population to the level of the estimates, or even to half of the latter, rejection of immigration would reach crisis proportions; the present favourable attitudes would be replaced by a policy of closing the doors, or at least very selective choice of immigrants and a very rigorous admission into the country.

Moreover, it is easy to foresee that such an attitude of rejection would affect not only the population of Italian stock – probably supported by the governments and public opinion of neighbouring countries, which would regard Italy as a bomb ready to explode in their backyard – but also by those strata of the population originating in the first waves of immigration.

In fact, it is quite clear that if it continued for years, a phenomenon as massive as that forecast by the UN would end up jeopardizing whatever the first immigrants had gained in terms of affluence and quality of life. This would be the result not only of the ‘political’ fear that the rejection crisis would also eventually affect those immigrants who at the beginning had been accepted without hostility, but also of the ‘economic’ fear of strong demographic pressure on Italian resources. Notwithstanding the ‘clearing-out’ effect of the quantitative decline in the population of Italian ‘stock’, these resources are definitely limited, whether in terms of housing, infrastructure or simply space.

Public Catastrophe, Private Tragedy

Thus, according to the most realistic predictions possible, one may conclude that there is no ‘demographic’ solution to the Italian crisis, but only a ‘political’ solution, in particular through reforms to the pension laws which would prolong the working age until 75. This would postpone the problem until about 2020. But beyond that date, one can very probably foresee a situation in which it will no longer be possible to maintain a decent level of pensions and an acceptable quality of standard ‘welfare state’ provisions. In other words, in a short time from now, Italian society will be incapable of feeding its numerous old people and of guaranteeing the medical care necessary to maintain them in good health.

In this, however, Italy will be a situation not very dissimilar to that in all European countries, including France. In fact, even if, in France, births stay slightly above of two children per woman, and thus correspond more or less to the reproductive rate needed to maintain the generations, such a rate is still completely insufficient to offset the destabilizing effects of longer life expectancy, a recent phenomenon which is of concern to France as much as to Italy. If, leaving aside immigration, it is predictable that the ratio between the active and inactive in Italy will go – by mid-century – from 4:1 to a little more than 1.5:1, in France it can be predicted this will be about 2:1.

Thus there is an imminent danger that in Italy the burden of taking care of the old will become too heavy for the government, and will largely come to fall upon the family and upon religious institutions, as used to happen before the introduction of the welfare state. The consequences could be dramatic since, once there has been a drastic reduction in expenditure on pensions and medical care, the problem of insufficient numbers in the generations of working-age relative to those who do not work will no longer be a collective problem for Italian society. It will be a problem for the family and individuals. In 2025, couples who today have one child – not to mention those who have none – will find themselves in an unsustainable situation, and the problem will inevitably be made worse by the fact that only 50 per cent of present-day couples, legal or de facto, will reach old age without separating, that is, without aggravating the complex problem of aid for old people living alone.

Consequently only a very small number of Italians who are today nearing old age will have enough offspring to be able to rely on the help of their own children. The severe planning put into practice by the ‘baby-boomers’ who launched the failed revolution of 1968 now risks turning against them, leaving them bare, alone, devoid of strength and help in the face of a society which appears to find it impossible to guarantee the goods and services which in the welfare state all Italians have grown accustomed to considering their personal right.

Without any doubt, it is possible to consider the hypothetical situation in which the excessive number of old people is brutally solved by a kind of ‘revolt of the slaves’ and a redistribution of power and resources from the ‘old’ to the ‘new’ Italians. Within a few decades the ‘old’ Italians – those who make up the Italian population in the strict sense – will be too weak and exhausted, too dependent on the support, including physical support, of their nurses and immigrant domestics, in any way to oppose the rebalancing of the economic and social security system to their disadvantage. This might mean an acceleration of the death-rate, and a drastic reduction of the ‘burden’ represented by decrepit ‘old Italians’.

The process might not be smooth, of course, as there will surely be one – or numerous – communities of ‘new Italians’ who will become active politically and claim their right not only to get rid of their defenceless hosts, but also to prevent new arrivals from abroad: a phenomenon that might be very similar to American ‘nativism’ at the end of the nineteenth century, when those who had become ‘natives ‘ of the North American continent opposed new waves of immigrants. In the New World as well, those who had become ‘natives’ were not of true ‘American stock’. They were British, Dutch and Scandinavian colonists who derived their ‘right’ to exclude new arrivals from that part of the world from the fact that they had been the first to exterminate the indigenous population and take control of their territory.

The presence of various immigrant communities in Italy – and not of one group in the absolute majority like the North Africans in France and the Turks in Germany – will certainly influence this process, even if it is not yet possible to predict in what way. It will perhaps delay the ‘power takeover’ by the ‘new Italians’, or it might lead to this being accompanied by disputes and fights between groups of different origins.

The Islam Factor

One of the main groups to play an important role in the Italy of the future will assuredly be the Muslims. This is made likely by a variety of factors, first of all, by the sheer number of Muslims in Italy. Already in March 2006, indeed, they numbered approximately one million out of a present total of about three million immigrants in Italy.

During the last two decades there has formed in Italy – without any significant socio-cultural or political reaction – a religious minority which would have been unthinkable even yesterday in a nation whose history is strongly bound to the history of Christianity. For a long time this did not create any serious problems; in fact, it went almost unnoticed, or was seen as a further contribution to the richness, variety and vitality of the Italian scene. Only in the last five years – in practice, since September 2001 – have there begun to emerge in Italy fears about the less positive aspects of the immigration phenomenon and the problem of the coexistence of very different habits and customs, along with occasional hostility as well.

Acknowledgement that immigrants practising the Muslim religion pose a problem beyond those surrounding immigrants of other cultures – European, African, Asian and, of course, South American – is a very recent phenomenon. This is why it is only very recently and incompletely that the idea – still not examined in depth – has started to emerge that it is a problem which would be better confronted at the moment of entry to the country, rather than when its most serious negative consequences make themselves felt.

This is especially true in Italy. In fact the liberal conviction has always prevailed in Italian public opinion that coexistence between people of different nationalities, traditions and religion does not pose an insoluble problem in itself, and that it is really possible to produce a ‘multicultural ‘ society without the human and social costs being too high.

Not much importance has been attached to ‘the nation’ as a factor because the Italians are not conscious of it themselves and find it difficult to imagine that it could exist for other peoples. It is the same for religion, because the majority of Italians are convinced they live in a ‘secularized’ society. And above all, there has been no desire to attach too much importance to the fact that the two religious traditions, Islamic and Christian, are different enough to impose moral codes which are sometimes antagonistic, but near enough not to be indifferent to each other and also to offer more than one field for quarrels and disputes.

Italian society – with a few exceptions in the North, in some Alpine valleys on the border with Switzerland – has been very open-minded in its relations with immigrants. This was very evident in the first stages of the inflow, and still is, especially south of the Appenines, where the impact of the hate campaign conducted by the Northern League has not been felt.

Undoubtedly, this welcoming attitude has been motivated by fresh memories of the time when Italians looked to Germany in more or less the same way as Moroccans look to Italy today. In addition, as a factor in reducing Italians’ feeling of the immigrant’s insuperable ‘foreignness’, there is their own weak consciousness of their cultural identity – on the contrary, almost an absence of the very concept of collective identity, as well as their lack of national pride and weak capacity to act in concert. These characteristics of Italian identity, which have always been a negative factor in their relations with other countries, whether in time of peace or war, have turned out to be positive when confronted with the new phenomenon of immigration, in particular Muslim immigration. They have been a moderating element in anti-Islamic propaganda, and thus a very useful factor in establishing good relations with the new arrivals.

In this respect, Italy can be seen as having, from a certain viewpoint, an ‘arm’s length advantage’ over other European countries, which in contrast are societies with a deep consciousness of themselves and their own identities, often to the point of being ridiculous and arrogant, and which have created invisible barriers to the integration of foreigners. But – and in order not to attribute to Italian society more merit than it deserves – it could be argued that the Italians’ watered-down ‘rejection’ of immigrants comes from the fact that immigration into the country has characteristics which make it less of a problem than in countries like France, Germany, or Britain. In particular as we have already pointed out, the immigrant community in Italy is characterized by the great diversity of national, ethnic and religious origin.

This is very clearly different from France, where immigration in the last forty years has created a relatively homogeneous block of several million people with a common North African origin, their own single language and a generalized but fairly homogeneous link with a great culture, that of the Arabs, as well as their own, Islamic, religious tradition. Thus, the immigrants in France have all the characteristics needed to form a separate nation.

Hardly less serious is Germany’s problem with several million Turks, who however are neither culturally nor in terms of religion and ethnic grouping as homogeneous or as strong as the Arabs. They have, however, been transformed into an foreign bloc, by being parked for decades in a kind of legal ‘no man’s land’ under the pretence that they are ‘Gastarbeiter’ or guest workers, even when they have been born and have grown up on the edges of large German cities. The difference with – and the advantage over – Britain is even more distinct. In that country, there is a significant minority of Pakistanis and Arabs who are very well integrated into economic life, but who are far less culturally assimilated than their French equivalents, and who are determined to assert their difference and identity to the point of giving rise to incidents like the 7 July 2005 bomb attacks in the London Underground and the fatwa pronounced against Salman Rushdie in 1988.

The results of differences in the composition of immigrant communities are easy to observe in public transport and at the workplace. In France, immigrants often speak Arabic among themselves, in Germany, Turkish, and in Britain, Urdu. In contrast, in Italy the immigrants speak most of the time a kind of crude and bizarre Italian among themselves. Certainly it is a much impoverished Italian, deformed, debased and simplified, a language from which the conditional and gerundive forms have disappeared, and in which everyone uses the familiar ‘ciao’, and addresses other people with ‘tu’ (for ‘you’), rather the more formal ‘lei’. It sounds a funny ‘pidgin Italian’ to an educated ear, but it is still Italian. Mutual understanding will doubtless improve with time, as both sides make an effort towards communicating with the other.

The Italians do not indeed perceive their language like the French, as a monument to be polished and preserved unchanged generation after generation, but more the way the English-speaking peoples do. The Italian language is – one might say – like a garden made of living and permanently growing plants, where new species can easily put root, and grafts happen all the time. A new Italian language is thus being born, together with the New Italians.

However, it may not be forever thus. In the long term, Italian policy towards Muslim immigration cannot avoid being influenced by the fears that this arouses in other countries with which the society on the Italian peninsula maintains a permanent cultural osmosis. As we have seen, the ageing of the population and the rapid decline in numbers to which Italian society is condemned makes it indispensable to introduce an increasing number of adult workers from abroad into the labour market. And some of the latter come from, and will inevitably continue to come from, countries which are geographically close and which have a population surplus. These are principally the Arab Muslim countries of North Africa.

Some rumours suggesting a ‘sigh of relief’ appeared at the margin of Italian politics, for example, among the ‘populists’ of the Northern League, when it became known that in the last few years the percentage of Christians among immigrants had exceeded 50 per cent, if only by a little. This has been due to the influx from eastern European countries that had joined or were on the point of joining the EU. But it can only be a temporary phenomenon. The former communist Europe from which the great majority of Christian immigrants originated does not in fact have the demographic resources to cope with Italy’s – and in general western Europe’s – workforce needs. Actually, in Romania and Ukraine, the very two countries that have been providing the main influx into Italy, the population is subject to a sharp decline and ageing process.

Coexistence with Immigration?

By now, Italians have been coexisting with immigration and its consequences for about twenty-five years. These issues have become the ones of which Italians are most aware, although it is a subject which is relatively little discussed as it is known to generate contradictory feelings, if not disputes. On the one hand, there undoubtedly exists in Italy a sense of solidarity with the immigrants, a sense of solidarity which is quite widespread, also for the good reason that there are not many other causes to stimulate moral involvement.

On the other hand, a sense of anxiety is appearing in daily life, the beginning of a certain ‘Angst’, a feeling which until now has been least characteristic of the Italian people. Finally, and most seriously, the Italians have been facing the necessity of coexisting with immigration without any real guidance, as their intellectuals have not undertaken a true analysis of the problem and their political leadership has not adopted a policy to tackle and control it.

In everyday matters, successive governments, and the state authorities in general, have gone about their dealings with immigrants in an uncertain fashion, passing theoretically stringent laws and then permitting mass exceptions, for ‘humanitarian’ reasons which are partly a pretext and which partly correspond to a significant body of public opinion, especially among the young, that is sympathetic to the immigrants. In effect, extra-legal situations have been created and tolerated, while the habit has spread of ‘making rules on the spot’, with successive laws and repeated amendments, which seems bound to cause more problems in the future than they solve today.

Neither the government authorities nor, if the truth be told, public opinion have really ever succeeded in finding the right balance between the different objectives to be followed in dealing with the influx of immigrants: satisfying the demand of humanitarian behaviour; putting this new labour force to productive use according to both their needs and the economic requirements of the host country; taking into account the political needs of public order. In no case has this been seen so clearly as when tens of thousands destitute Albanians arrived en masse in Apulia, the heel of the Italian ‘boot’, aboard two incredibly over-crowded ships. The first wave was accepted with excessive benevolence while, a short while later, the second was rejected with equally excessive harshness.

If the laws and policies concerning immigrants have been improvised and patchy, it is not only because Italy had no previous experience in dealing with immigration, but also because there has not been a calm and realistic debate on the subject. Furthermore, public opinion has only recently appeared really to be worried enough by these problems for the question of immigration to have become a new cause of political debate and discussion about the economic problems which such a phenomenon is bound to bring with it in the long term. Skirmishes among politicians and interest groups have instead prevailed with, at least so far, a clear majority of the political and economic forces of society in favour of the ever-growing inflow of outsiders.

The Pro-Immigration Lobby

Confindustria – the Confederation of Italian manufacturing industry – is normally cited as one of the organizations which appear to favour an ‘open door’ policy. And indeed, in a ‘normal’ year, it requires the admission of some hundred thousand new immigrants – which is nearly double the government’s forecast – especially to work in sectors refused by Italians. Plainly, this is a requirement for people able to work, a requirement for labourers to be employed full time in factories, and does not take into account families.

On the top of that, it comes as no surprise that there are more active organizations such as Confagricoltura, the Farmers’ Confederation. At the end of every winter, they apply vociferous and strong pressure for the admission into Italy of seasonal workers without whom, they repeat every year, the early fruit and vegetable harvest would collapse. Employers in the tourist sector join in with reverse seasonal requirements.

The position of Confindustria and of the farmers’ and hoteliers’ organizations is very understandable. They represent the economic interests which have always gained from the presence of immigrants and which made up the initial hard core of the pro-immigration lobby. But later, the impact of immigrants as consumers of goods and services, which did not seem to be very relevant in the last years of the past century, has become more significant. From an initial stage, in which the only sectors positively affected were the used-car business, plus some illegal activities, and the rent markets in areas of deteriorating housing,[i][2] the most recent developments have shown the positive economic consequences of immigrants becoming settled.

Thus, in 2005 and 2006, around 13 per cent of all residential units were sold to immigrants, an amount that looks disproportionate if one thinks that they represent only 3 per cent of the total population, but a percentage more or less in line with the share of their contribution to the total number of births in Italy. In short, the number is the result of the fact that immigrants represent a young and fertile component of Italian society which tends to create families, have children, settle in the country and invest in real estate that they have largely contributed to build (construction obviously being one of the sectors that has most recourse to immigrant semi-skilled labour).

Being usually young – some immigrants who arrive alone are even in their teens – they obviously are a healthy component of the Italian population. A rough assessment of the relationship to the national health service has come to the conclusion that an immigrant contributes to it about €1,000 a year, getting back – in services and drugs – around €600 (one-third of this in assistance to pregnant women and newborn babies). Thus only the fact that hospitals are a public service prevents them from being part of the pro-immigration lobby.

On the other hand, there are no sectors threatened by immigration. If one excludes the hawkers and souvenir sellers in Florence who, several years ago, rioted against immigrant peddlers at the cost of the lives of three unfortunate Moroccans, it seems clear that the immigrants move into sectors abandoned by Italians or sectors which are in such strong expansion, like the catering trade, that the explosion is absorbed without shocks (for example, the Chinese restaurant business).[ii][3]

The costs to society

If there is no conflict, between immigrants and Italians on the labour market, other problems do exist. Some have recently started to appear in the relationship with the immigrants of Chinese extraction are indeed due to other reasons, namely to the fact that the Chinese are rapidly becoming – as a community – a semi-autonomous component of the Italian society. They are indeed hard workers, and even more tenacious savers. If he case of Prato – the “capital” of the Italian garment industry, where the local Chamber of Commerce calculates the presence of over 16,000 Chinese-owned businesses – is certainly an extreme one, their presence is becoming to be felt al over the country.

The Chinese tend indeed to invest their surplus income in the purchase of buildings in the commercial districts of the large cities, and they either rent them to the immigrants of other origin (sometimes, under execrable conditions of hygiene) or use them to carry on activities – such as wholesale – which normally should be located in more suburban areas. These are very profitable activities, but also activities that bring about a quick degradation the surrounding urban environment. The “Chinatowns” of Rome, Milan and Naples start to be an alarming testimony for it. Moreover, when the authorities try to enforce laws and municipal regulations, the Chinese have sometimes recourse to violence, and at the same time ask for the protection of the Peijing government, whose representatives in Italy willingly provide their active support.

Still more serious are some other aspects. First of all, the fact that this component of immigration, in spite of being very well integrated from an economic viewpoint, shows only few signs of its intention to be assimilated into the Italian society. Second, that it is organized internally in secret groups, that do not hesitate to exert violence against its own members when conflicts of interest arise. Many Chinese, namely the younger generations, seems to appreciate the advantages, the opportunities and the freedoms that one can enjoy by becoming Italian in full, but the majority resist the assimilation, and could thus become a problem comparable with that of the nomads originating in Eastern Europe, the so-called “Roms”, that until recently were referred to as “gypsies”. The members of this category – an even more closed community –, while benefiting from the laws on immigration, cannot however be regarded as immigrants, because they are not integrated economically, and cannot be, as they do not carry on – nor seek, with some exceptions – any productive activity. Around their camps – that the authorities seek, but without much success, to make stable by the provision of essential services – situations of tension and incidents are the rule. Thus, in the spring of 2007, in central Italy, what remained of a camping was set to flames by somebody unknown, a few days after being abandoned in the outmost hurry by a tribe of “Roms”, to which a belonged a driver that, in a state of alcoholic intoxication, had killed four children of a nearby neighbourhood.

Immigration policy and politics

It must be said that the employers’ organizations are only one of the components in the line-up seeking the opening of Italian society to migratory movements, and they are not even the most vocal and active. On the contrary, the attitude most favourable to making it easier to cross frontiers comes from the political left and above all from Catholic organizations. In the case of the latter, it is easy to understand the ethical imperative that is well known for its frequent expression in well-intentioned small actions, while remaining incapable of seeing what are the long-term complexities of immigration. This has been a problem of historical importance for western society.[iii][4]

It remains however to be explained why it is the left-wing political forces – the very forces that should represent the social classes most directly economically threatened and whose lifestyle is daily damaged by immigration – that have created a real ‘pro-immigration lobby’. Their political stance is indeed one of ‘opening the door wide’, which claims the indiscriminate granting of rights to the ‘new Italians’. Above all, the progressive parties are at the origin of the repeated amendments of regulations on behalf of illegal immigrants, amendments that have spread around the whole Third World the idea that Italy is the soft underbelly of Europe, the promised land for all destitute people, that the important thing is to get into the country, legally or otherwise and, once in, ‘things will be fixed’ by joining in one of the periodic ‘regularizations’ of semi-illegal immigrants.

In a crude attempt to exploit the backlash from the immigration phenomenon, that is, the growing irritation and nascent xenophobia among workers in the north-east, some groups on the extreme right have no hesitation in advancing the explanation that the left, having lost the support of the Italian electorate, aims to let millions of immigrants into the country so that they will form a reservoir of voters once they have become citizens.

This clearly is an absurd explanation. It is true that in the dying years of the last century, Livia Turco, the Minister for Social Affairs, proposed giving the vote to immigrants quickly. But this proposal was limited to communal, regional and provincial elections only.[5] And Turco was evidently inspired by a political commitment to treating immigrants as people, not just numbers; an inspiration which undoubtedly corresponded, and corresponds, to an ethical and egalitarian demand which is traditional in socialist political groups, and which the recent transformation of world politics has not been able to suffocate. In short, Turco’s point of view revived, in a positive sense, Max Frisch’s famous conclusion about Switzerland’s experience with immigration.

The explanation of the commitment to immigration of left-leaning political forces must be sought closer to hand. It must be sought first of all in the fact that the political left is the natural electoral representative of those strata of public opinion who most painfully feel the lack of values in contemporary Italian society and generally in western society. And this part of the public, which consists widely of young people, sees solidarity with the immigrants as one of very few opportunities for moral engagement, even if most young people are often ill-equipped to understand the problems which the influx of immigrants brings to the host society, or the true requirements and aspirations of people who come from such distant and different countries, and whose life has suddenly been so traumatically torn apart. These strata of the population and the electorate are larger than the cynicism of the media would have us believe, and they form the better part of a pro-immigration lobby which the political class feels must be taken into account.

It is only too obvious that – to balance the benefits of an influx of immigrants – there are, in the Italian economy and society, non-negligible costs as well. These costs are typically ‘externalities’, that is, they fall to be paid outside of the enterprise to which the working immigrant is providing their labour. It is all about the cost of the social welfare problems caused by the ‘men’ who moved from one country to another in order to bring the ‘force of his right arm’, which is necessary and very useful to the enterprise. These men, when outside the factory where they work, must sleep, eat, look after themselves. They must fill their spare time and satisfy their religious, cultural and moral needs. And thus begin the problems and the costs to the host country.

In the cases in which the family has come along with, or has joined the worker, a part of these needs will be satisfied within it. But the family is the cause of more problems, as its presence compounds the number of men and women to be accommodated in a society very different from that of origin. And while the worker himself learns a lot about the host society and its habits while at the workplace, the same does not apply for wives and children. Their presence imposes instead new problems in new fields, education first of all, but also in the areas of leisure activities, drugs and youth crime.

The sum of all these problems is the physical and economic ‘disintegration’ of the areas in which immigrants are concentrated, a degeneration the price of which is mainly paid by the people who lived in these areas before the immigrants arrived. And it certainly will not be the central or ‘good’, upmarket areas of the cities which will feel the biggest impact, but above all the areas where the mass of people live. Thus, to physical and economic and social degeneration – typically represented by formation of bands of child thieves – can also be added the ‘political degeneration’ deriving from the reactions of these social classes which will rapidly give birth to extreme and xenophobic political positions. An opinion poll – conducted by a foundation operating in the north-east of Italy, where the Northern League is active – found that 43 per cent of Italians believe that immigrants are ‘a threat to public order and personal security’, and that as many as 60 per cent have concluded that ‘The country is no longer able to accept immigrants, even legal ones.’

This conflict of interests affects all of Italian society and is the determining factor in the approach of all political parties. The impetus from the employers and above all the pro-immigration lobby had in fact brought the centre-left government to an immigration policy which had or should have had implications for three areas of government action in this field: programmed entry with fixed annual quotas (based upon objectives relevant to the structure of the population and the composition of the workforce), a more efficient fight against clandestine immigration and criminal exploitation of immigrants, and support for immigrants’ integration into Italian society.

It is easy to confirm that, with the introduction of another immigration law (Bossi-Fini) by the centre-right government which had followed the centre-left, neither the second of these intentions, much less the first, was translated into reality, while the initiatives for integration of immigrants and the related expense proliferated like a cancer.

As can be seen, the political attitudes of the Italian about immigration are very different from that of the country’s European partners. This is primarily the result of the already mentioned lack of a strong sense of national identity in post-fascist Italy: a feature that makes it impossible in Italy for there to be the sort of extremely violent reactions to immigration that, especially since the Madrid attacks, have been occurring periodically in Spain, a country where national feeling is in contrast quite strong.

The comparison with Spain is interesting because, like Italy, it is a country which has only recently been subject to a wave of immigration. The differences with the other European countries come from the fact that the social fabric in North-West Europe has by now been so profoundly modified by decade after decade of immigration that these countries are bound to political attitudes which are not yet prevalent in Italy.

In France, for example, the country which, from legal/administrative and political perspectives, is the most like Italy, it is clear that the number of voters of recent migrant origin is so high as to make it difficult to have a simple approach to the problem. There is a large bloc of voters with feelings of solidarity and definite fears when it comes to immigration policy, and thus there are those who shun excessively severe positions, while others go to extremes. Part of the Front National’s electoral support comes from people of purely French stock, who are driven by feelings which are to a greater or lesser degree racist. But another firm section of its support is to be found among recently naturalized French, who exhibit extremist feelings in an effort to appear more French than the French. In so doing, they seek legitimacy in their own eyes and believe they gain legitimacy in the eyes of others.

This basic difference in its situation makes it difficult for Italy to adjust to any immigration policy agreed with its community partners in Brussels. Italy’s weaknesses (such as undeveloped national feeling) and Italy’s strong points (such as the recent immigration phenomenon) clearly make it expedient that immigration policy should remain a national policy for all of the predictable future.

Men or Labour?

The cluster of questions revolving around immigration is strongly political in its nature, but not just in the squalid sense of creating a framework of dependents for small-time politicians. It is political in the sense that for Italian society, as for all societies which have an influx of immigrants, the arrival of a mass of labourers, mostly men, from the Third World brings with it the need for some hard choices. The first choice – which is the most important but also the one of which public opinion is least aware – concerns the strategy of the very aims of immigration policy. Another choice, tactical in nature, concerns the tools and methods of this policy. And, as it lends itself to the facile electoral demagogue, this choice is the one which causes the most fuss.

So far as the policy aims are concerned, firm distinctions must be made between two major problems tied to the immigration phenomenon, and which can already be glimpsed in existing legislation: the problems of our country’s demographic decline and that of the availability of the workforce.

To compensate for demographic collapse, that is, for the lack of men and women, brought about by the drop in fertility levels to half of that required to re-create the population, it is first necessary to define a long-term ‘population policy’, which should take account of the fact that a reduction in the total number of inhabitants would not perforce be a reduction in Italy’s ‘power’ but, on the contrary, would eventually improve the quality of life. On the other hand, in order to deal with the quantitative ratio between active and inactive members of the population, that is, to deal with the lack of labour, a different and separate policy is needed, a ‘workforce policy’, aimed at bringing about immediate results.

It is easy to see that the two policies, for population and workforce, have different technical requirements as well as different objectives. And even if the lack of labour force is partly also a result of Italy’s demographic collapse (but only partly, given that Italians will not do certain jobs), it would be impossible even with a big demographic programme over many years to expand the workforce by increasing the number of births per woman. In short, dealing with the demands of the system of production means that recourse to immigrants, ‘ready to work’ adults, is inevitable, and not only to fill the jobs refused by Italians but also for many new types of work.[iv][6]

Immigration will, however, not suffice. In fact, the more rapid their entry into Italian society, the more the behaviour of the immigrants will come to resemble that of the local population. Thus the immigrants’ availability to take on jobs refused by Italians, and their willingness purely and simply to be exploited in terms of working conditions and schedules, will decrease rapidly.

The Arms, not the Soul

Italy’s economy needs labour and immigration provides it. Labour, however, never comes all by itself. With it – the ‘working right arm’ – come inevitably men and women. And it is then that the problems we have been describing come together, and the facts of being a poor man exposed to all the charm and temptations of an affluent society, of being a stranger in a potentially hostile environment, of being an immigrant competing for work and shelter with the poorest of the natives, of being a Muslim living among the infidels, of being a lonely man away from home, begin to form a knot difficult to untie.

As long as one is just a worker, ‘selling the strength of his right arm’, integration is very easy. Generally speaking, the company and the working environment immediately create homogeneity and coordination in gesture and deed, timing, activities, needs and behaviour. In addition, since the immigrant has come with the sole aim of making a bit of money, he tends to devote as many hours of the day to work as possible. It is outside the workplace that the problems begin, for it is there that the needs and behaviour of men take over from the uses and functionality of labour.

At work, a Muslim immigrant can hammer, cut, sew, fix parts together, or cast steel just like a non-Muslim. But when he is away from work he must eat meals prepared according to the rules of Islam, resist the temptation to drink like westerners or avoid drinks the effects of which he is not used to controlling. In his non-working hours, he ends up ‘entertaining himself’ in ways to which he is unaccustomed, and has social relations – especially with the opposite sex – which follow far more liberal rules than those of his original society. For the Muslim immigrant, the shock of European-style social relations is both extremely violent and tempting, if only for their great freedom and the absence of state control. He has the feeling that, by coming to work among the infidels, he is trading for money not only the strength of his right arm, but the whole of his personality, including his soul. The Muslim immigrant can avoid such problems and complications only if he comes away from work totally exhausted, and sleeps the sleep of the dead until it is time to return to work.

This, of course, applies to the immigrant who is single. For, as we have already mentioned, when there is a woman and a family behind every pair of hands, the problems increase exponentially and take on complex moral aspects that finally interfere with the work itself. How can the immigrant worker ever concentrate fully on his job when he knows that away from his workplace the women of his family are exposed to all the corrupting temptations of a society that seems to him to be profoundly immoral from the sexual and family perspective?

And how can he work long hours, when he has reason to fear that his children are absorbing the values of a world in which there is no more respect for parents and old people? And if, on the contrary, he knows that his children react negatively to their new environment how can this labourer devote himself totally to his job knowing that there is a risk of his son’s becoming an anti-western fanatic prepared to destroy himself and others? Were the London Underground suicide bombers maybe not the children of immigrants, and not first-generation ones? And was it not the children and descendants of ‘new Frenchmen’, who seemed to be more or less successfully integrated culturally, the ones who brought turmoil to the life of the French city-suburbs for three weeks?

Although few Europeans realize it, even when the Muslim immigrant is economically integrated, even when he enjoys a decent income and some social services inconceivable in his home country, he does not live in tranquillity. On the contrary, the Muslim immigrant in Europe lives in a situation of fear and anxiety over ‘cultural contamination’ and its consequences very similar to, if not greater than, the anxiety felt among the most ill-informed and susceptible sections of the European population. And his fears are much more firmly based than those which are spread in Italian public opinion by the most virulent critics of immigration, namely by journalists imported from the Middle East, and in general by the most ill-bred parts of the right-wing press.

It is fear that pushes the Muslim, or other, immigrants to request the authorities in the host country to recognize his own cultural identity. What he seeks is a sort of endorsement of an irremovable quantum of the very ‘diversity’ that endangers him from moment to moment. It is again fear that is behind the tendency for the Muslim immigrant living in partibus infidelium that pushes him to prefer living inside a ghetto, that in some vague way reminds him of his cultural community. There are understandable reasons why he is inclined to defend his own identity.

Actually, what is pushing him to assert his difference, and to ask the host country to recognize his right to be ‘different’, are the same reasons as those which lead more than one journalist and more than one European politician to ask him to integrate, to deny himself, to abdicate, or at least conceal his faith, the way the Jewish ‘Marrans’ and the Muslim Moriscos had to do under Torquemada. In short, the Europeans ask the immigrants to behave in such a way as not to frighten them. Alas, no one – with the exception, it seems, of the Abu Ghraib torturers who exploited it in depth – has realized that these men are timid and chaste, and for them the mere presence of women causes profound embarrassment. The Muslim immigrant in our cities feels lost and uneasy, and he is as afraid of us as we are afraid of him. This negative symmetry does not make relations easy. On the contrary, it can create a very dangerous situation, in which all irrational and unforeseeable behaviour becomes possible.

We Europeans too often forget this aspect of immigration, the fact that human beings are involved as well as labour. We do not imagine, indeed it does not even enter our heads, that immigrants have their own morality, their own sense of personal honour and dignity which is expressed in a very different way from ours. We do not realize that Muslims, even when they come from countries which proclaim themselves ‘revolutionary’, in reality are the trustees of a mentality which is primitive in some things (namely, concerning relations between the sexes), but very delicate and fragile under other respects, and above all extremely conservative, much more conservative than that of any European. And that they give an extremely severe judgement of our society, of our being de-Christianized, of the laxity of our customs, of our treatment of our elders.

Our negligence and incomprehension is what sometimes provokes hostility in our relations with them, most forcefully from western conservative political forces. And this is all the more paradoxical as, if his political vision stretched further than the end of his nose, a true western conservative ought to see them as natural allies. A true Italian conservative, rather than calling for help, should probably ask himself whether the spread of new conservative trends in Italian society which go hand in hand with its ageing, do not make it possible to come up with an immigration policy that meets the demands of both sides. Such a policy would need to create the tools to allow the immigrant to profit fully from the work potential which Italy offers, while discouraging everything that produces insoluble problems for social integration.

In partibus infidelium

It is easy to predict that the distinction between the needs of the labour market and those of population structure, the difference between ‘labour’ and ‘men’, will provoke many negative reactions and these will be paraded in every egalitarian and supposedly humanistic argument. It will be said, with reason, that the two things cannot be separated and that to see immigrants only as a labour force is a negation of their humanity, a violation of the ethical principles that demand that a man should never be considered as a means but always as an end in himself.

But it is easy to reply by emphasizing how, given all the understanding and readiness which people claim to show towards immigrants, no one has ever taken the trouble to try and see how they themselves, the people most directly affected, perceive the phenomenon of immigration, and whether or not they are interested in integration with Italian culture. Everyone in our society can see the presence of the incomer, but it occurs to almost no one that in order to come among us he first of all has to have emigrated, and is someone who has been torn away from his own country and culture by economic exigencies. Almost no one allows for the fact that when the immigrant arrives he is already profoundly marked by this severance. Not by chance do the Muslims of North Africa who make up the majority of immigrants to Europe call emigration ‘elghorba’, ‘the exile’.

If anyone had been bothered to understand how the immigrants see their own circumstances, their feeling of belonging to the society they have left and the feeling of diversity towards that in which they have arrived, it would have been simple to ascertain that immigrants themselves make a clear distinction between ‘labour’ and ‘men’, between their readiness (and ambition) to become part of the workforce in the country to which they travel, and the much more painful process of ceasing to be that which they are, in order to become Italian (or French, or Spanish). In this context, it is of very great interest to see the distinction which Moroccan immigrants in France make between the ‘green passport’ (the Moroccan passport which is seen as a kind of permission to leave the country and go to work abroad), the ‘blue passport’ (which French citizenship used to confer, and which was seen as the sentencing to the loss of one’s own identity), and the most recent ‘brown passport’, indicating the European Community, which is seen as a true guarantee of freedom because it permits the holder to live and work in a free-market, free-movement area which is not defined in cultural and national terms, where everyone can be himself and it is possible to earn one’s living without having to pretend to be what one is not.

Anyone who had taken the trouble to understand the thinking of the immigrants which they claimed to be concerned about, could also have easily found out what are immigrant’s real priorities. They are a lot less interested in their families joining them than the Italian authorities believe, and especially a lot less than many Italians who see immigrants as future Italians, and are convinced that one day there will be erected on a beach in the island of Lampedusa (the point of Italian territory nearest to the African coast) a monument to the disembarkation of the ‘barefoot armada’ that came to rescue Italy’s population from decline. In fact, the majority of immigrants are single men who set out in the belief they will stay abroad only for a more or less short period of time, and whose most ardent ambition is to return home with some savings, to live according to their own customs. They are certainly not longing to be assimilated in western society, and even less to bring their own families to be assimilated also.

In reality, the majority of those who face ‘exile’ alone, thinking they will remain abroad only for a short period, nurture as their most keen desire that of returning to their village not only to enjoy their family life, but most of all in order display the tiny affluence they have gained as the price of the sacrifice of emigration to those who saw them suffering hunger before they left. They certainly do not leave with the intention of assimilating into western society, and even less of bringing their own family to be assimilated also. This applies most of all to immigrants from North Africa – whose morality is especially rigid in family and sexual matters – but not only to them.

For the Senegalese, who are also Muslims, but from a society where sexual morality is less strict, the lack of interest in putting down roots in Italy is – if possible – even stronger. Senegalese immigrants, who can be seen on every street corner in Italian cities, are not individuals who are adrift and who seek to make a place in someone else’s home. On the contrary, they are part of a very efficient and well-structured network of hawkers who belong to a Muslim brotherhood, the Muridya, which manages and helps young people enter the world of work in Senegal, usually the commercial sector, after they put together a little savings on the international hawkers’ circuit. The elders who give spiritual direction to the brotherhood from the mosques in Touba in Senegal certainly do not want to see them integrated with Italian society, a society with which their relationship is moreover excellent, perhaps the best among all the immigrant communities, but which is nevertheless still a different and foreign one.

The provincialism of Europeans, not to mention that of Americans, is such that they see the Muslim immigrant as someone who wants to steal their jobs, their houses and their country. The average American or European believes that no human being could wish for anything other than to become like them. They can’t imagine that the majority of Muslims despise the West as well as fearing it, as even the new Pope Benedict XVI has noticed. For Muslims, the freedom they enjoy, in all senses of the word, in Italy and in Europe is very close to moral ruin, and is thus ‘excessive’. And they see us less as a lay society than as a society which has dramatically lost contact with the common God.

There are therefore also moral reasons, and not only economic ones, for the Muslim immigrant to prefer to leave his family behind, in his home country. To be sure the economic reasons are extremely important. Indeed, with the small sum of money even a precarious job has allowed him to save after a few months in Europe, an immigrant can secure for his family (and for himself when he returns at harvest time) a style of life which, in his home country, appears affluent, with all the advantages it gives him, a better social standing for his children and the respect which his society accords to the image of the person who has achieved a certain success abroad. His meagre savings are a fortune there, while in Italy they would be small change, too little to feed his family, let alone securing somewhere to live other than a shack in some quarter peopled with drug dealers, transvestites and prostitutes.

In this context, German policy towards the Gastarbeiter is instructive, especially for its failings. It started from the premise that it was more or less impossible to become German, and that the foreign worker should maintain a link with his country of origin so that one day he could return there. This policy however rapidly contradicted itself. Germany has in fact accepted that it should play ‘host’ to the workers’ families as well and that their children should be born and should grow up in Germany. However, in its handling of these de facto roots, the German Federal Republic for a long time stubbornly took a legal position which treated both the worker and all his family as Wandervogel, ‘birds of passage’.

The temporizing and wavering typical of the ‘host country’ were thus set in theory but denied in practice, and became a fiction, creating a problem which became increasingly worse with time and turned out to be extremely difficult to solve.

The Creak of the Closing Gate

If all this were true, one could object, how do you then explain certain traits of behaviour among the Muslims who live in Italy? If immigrants from the Maghreb countries, the nearest geographically and the furthest culturally from which the influx originates, truly preferred to come and sell their labour for quite short periods, when they were forced to survive in highly straitened circumstances, and returning home at intervals with trifling savings, why is it that a lot of them end up with their families rejoining them, as encouraged by Italian law?

The answer is clear and immediate; because in Italy and to a lesser degree in the rest of Europe, too many immigrants live in a situation in which their rights are very uncertain. So far as the future is concerned, they are in a permanently uncertain state, because in the space of twenty years Italy has seen four immigration laws and something like six mass regularizations. Actually, the majority of immigrants entered the country irregularly and are working without secure rights, but on the basis that the important thing is to enter Italy and wait for a law to regularize any irregularity.

The widespread feeling in the Third World that being in Italy physically counts for more than the legal position reinforces this state of insecurity. In fact, from the moment he returns home, the immigrant is always in fear that he might be prevented from re-entering Italy. He knows that this is an improbable scenario, but the stake is too serious for him to take the risk. He cannot live decently as a ‘man’ in Morocco or Tunisia and look after his family unless he can be sure of selling his ‘hands’ in Italy where their value on the labour market is incomparably higher than in the Maghreb countries.

It is the alternative between staying ‘shut inside’ with no possibility of being able to return home or remaining outside of Italy that drives the immigrant to consider an intrinsically aberrant idea, moving his family. He knows that this decision means definitive uprooting, that once the women in his family will have tasted the European way of life they will oppose with all their might any idea of returning home. He knows that, when he will be at the age of retirement, of returning home to enjoy the fruits of his sacrifices, his children will be at a stage in their life when the opportunities offered by the western society will appear within their reach. He knows that his sons and daughters will be exposed much more than at home to the risk of drugs, criminal behaviour, prostitution, and so on.

He knows that moving his family away from his country of origin to the country in which he has a job will mark the beginning of a series of terrible economic difficulties for himself and his family. But he still prefers this alternative to the risks of not moving; and – given the way in which the situation appears to him – his behaviour is rational. And for Italian society his decision marks the beginning of all kinds of problems, in suburban neighbourhoods and on the sidewalks of major cities, in schools and in mosques, in juvenile courts and in reform institutions: all problems which at first look small and unlikely, but then grow more and more formidable the more immigrants there are, and the more uprooted and non-integrated they are.

This fear of being shut out of the country where the immigrant has found work is naturally aggravated each time some common-or-garden little politician from the Lega del Nord seeking popular favour starts bawling out ‘Enough immigration!’ And this fear provokes a decision taken reluctantly, not only because of the moral and material costs which follow, but also because of their loss of status. It is indeed well known that, when they periodically return home, immigrants enjoy the pleasure of showing off and boasting to their families and acquaintances about their successes, much inflated for an audience who only knows by hearsay the marvels of Europe. Moving the family therefore means suddenly finding oneself forced to reveal all the misery of the true situation.

The threat of a ban on immigration, campaigns by the gutter press to stir up religious and racial hatred, stupid rumours put about by those seeking popular acclaim by opposing immigration, the creaking of gates which threaten to close, all encourage a race to enter before it is too late, even if the immigrant is in no way prepared to provide decent conditions for his family. Thus, one should not be surprised that such a hasty and badly prepared transfer means that the family ends up living in disintegrating outer city edges among all sorts of marginal people. One should not be surprised that the children, male and female, in an environment where their own moral code does not apply, and in which they are lacking any cultural endowment to help them resist contamination, finally take to working the pavement and the drugs traffic.

Rights, not Fear

Contrariwise, were there reliable legislation and a framework of secure, irrevocable rights, it would be possible for the immigrant and especially the Muslim to be fully satisfied to offer himself to Italian society simply as a worker. It would be enough for him to be certain that once he had passed through the inevitable filter needed to select those who can be integrated into the Italian workforce he would have gained the right to enter and leave Italy when he wished, on the condition of respecting the criminal code.

We have seen that this solution would also serve the interests of the host country. Obviously, the important immigrant community which has already settled in the peninsula should enjoy all the rights Italians have, and be fully protected by the law. But new work permits allowing entry and exit would be given exclusively to those seeking professional activity and having the real capacity to pursue it, thus creating an incentive to look for an alternation of periods of work in Italy and regular trips home.