Trump, Myanmar, China

and the inheritance of Obama’s “dumb deals”

Just a few days after entering the White House, and a very recent convert to geo-political affairs, President Trump was obviously unaware of the plan that there was behind the US-Australian refugee deal. And couldn’t appreciate the political meaning and value to US diplomacy of taking 1,250 Muslims on US soil.

“I will study this dumb deal”, a just-elected Trump said in early 2017, at the end of a very quarrelsome conversation with Australian PM Malcom Turnbull, who had mentioned an Obama-era agreement by which Washington has accepted to take and resettle in the US 1,250 Muslim refugees, mainly of Rohingya ethnicity, that where at that time stranded in two detention camps in Nauru and Manus, near the coast of Papua-New Guinea.

And indeed he should, he should have studied the question before improvising a discussion with the more experienced Mr. Turnbull. Because, if he had refused to keep Obama’s engagements, and resettle the refugees, he might have done a big favor to the very country that he has identified as the main object of American hostility: the People’s Republic of China.

In order to understand what there was behind this story, and why Trump should have avoided, at least in this occasion, to express his well known stand about too many refugees coming in the USA, one has to take two steps back to the complex situation in was at the time – and still is – prevailing in the country most of these refugees come from: Myanmar, also know – since the times of the British Empire – as Burma. An ethnically very complex country, ridden by decades long wars among tribal and minority armies, and strategically located between China and the Indian Ocean.

First step back: Burma

Since the mid 20th century, Myanmar geographical location, coupled with the political consequences of the Second World War, that had brought about (a) the end of the British Empire, (b) the defeat of Japan, and © the triumph of Mao’s Communist Party in China, had made that the country had lived in Beijing’s shadow. Only relatively recently, in April 2016, a landslide in the first democratic election ever held in the country had brought about a “regime change”, and succeed in making the famous Nobel Peace Prize holder Aung San Suu Ky the de-facto ruler of the country. And has dealt a little-known blow to the People’s Republic of China. A little-known blow, but an extremely serious and dangerous one in both, political/prestige, and economic-strategic terms.

In order to assess the blow to China from a prestige and political viewpoint, one has indeed to look at Ms Aung San Suu Ky family background. Not only she has openly shown her preference for the West by marrying a Briton, and letting her children to keep being British subjects. Her Burmese side is also very meaningful; actually, much more meaningful. Because her father, thakin (i.e Master, a title with a clear racist connotation) Aung San, who is still today considered the “Father of the Nation”, had been in 1938 the founder (and for three years the Political Secretary) of the Burmese Communist Party, but had changed side in 1941, and had become the Chief of the Burmese forces fighting on Japan’s side in World War II.

It has to be said that he probably did that out of misguided patriotism, as he probably had become convinced that the Japanese were the only force that could free Asia, and his country, from British colonial rule. But his anti-colonialist engagement brought him too far: as far as accepting to be decorated by the Mikado himself with the highest Japanese military honors: something the Chinese – who were then under ferocious Japanese oppression – have obviously not forgotten. As hadn’t forgotten Lord Mountbatten, who managed to have him assassinated in 1947, as soon as he was back as the last Vice-Roy of India, and just before the independence and partition of the Raj.

All this added up, in the eyes of most Asians, if not all of them, to a fairly obvious conclusion: with Aung San Suu Ky rise to power, “regime change” had moved Myanmar from the Chinese sphere of influences, to that of Japan. And this, at the very time when, in Tokyo, the helm was in the hands of a new Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, who had been working to expand the international role of Japan, as well as of the country’s Self Defence Forces, in the framework of a “re-interpretation” of the post-war pacifist Constitution, and enable Tokyo’s army to “come to the aid” of other nations, even if Japan itself is not under attack.

Second step back: China

From an economic and strategic viewpoint, Myanmar’s shift towards the area of influence of countries (not only Japan, but its allies as well, including the US) that seem every single day closer to the possibility of becoming hostile to Beijing, would present more than just a danger: actually, it would be an immediate and serious loss, as it risks drastically reduceing China’s access to the Indian Ocean.

To fully measure the risk China faces with a pro-western Burma, one ha to put for a moment aside all the fuss about the South China Sea, about its islands (natural and man-made), and about the conflicting claims of all the countries that touch at its waters. The harsh reality is indeed that, from a geo-strategic viewpoint, China is locked in trap; and would stay trapped even if Beijing got its way in all of the disputes, actual or possible about the islands and reefs of that sea. The great Chinese ports are all on a closed sea, and oil tankers as well as all big ships, not to mention aircraft carriers and very big submarines, have only three possible ways of accessing international waters: the International Malacca Strait; and the Sunda and Lubbock channels, which are in Indonesian national waters. In simple words, even in times of peace, China suffers from a dramatic strategic inferiority.

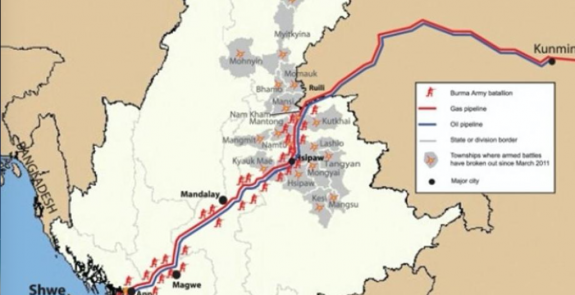

Friendly relations with Myanmar, are therefore of outmost importance for China, in order to access, albeit indirectly, to the open seas. To that aim, before Aung’s arrival to power, late in 2015, both an oil and a gas pipeline, that had been agreed between the two countries back in December 2008, had begun operating. Both are giant undertaking, technologically as well as politically, that run through two of Southeast Asia’s political hotspots, the Rakhine and Shan States, which retain semi-autonomous armies and have only just recently been nominally pacified.

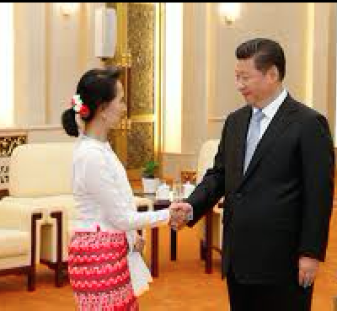

As some of the rebel tribes are culturally very close to the Chinese, Beijing has in part the key to real pacification, so that the new Burmese regime has shown a considerable degree of availability to good neighborhood relations. In mid-2016, a state visit to China by Aung San Suu Ky has given the impression that, in spite of the huge political debt she has with western political forces, and mostly with the media, for her rise to power – she doesn’t want Myanmar to be in America’s or anybody else’s exclusive area of influence. She might actually harbor the same patriotic feelings as her father, and thus an intention to keep good relations not only with the forces that have sponsored her access to power, but with China as well. Which would possibly entail expanding the infrastructural system that provides Burma’s eastern neighbor permanent access to the Indian Ocean

The Rahingya “moral imperative”

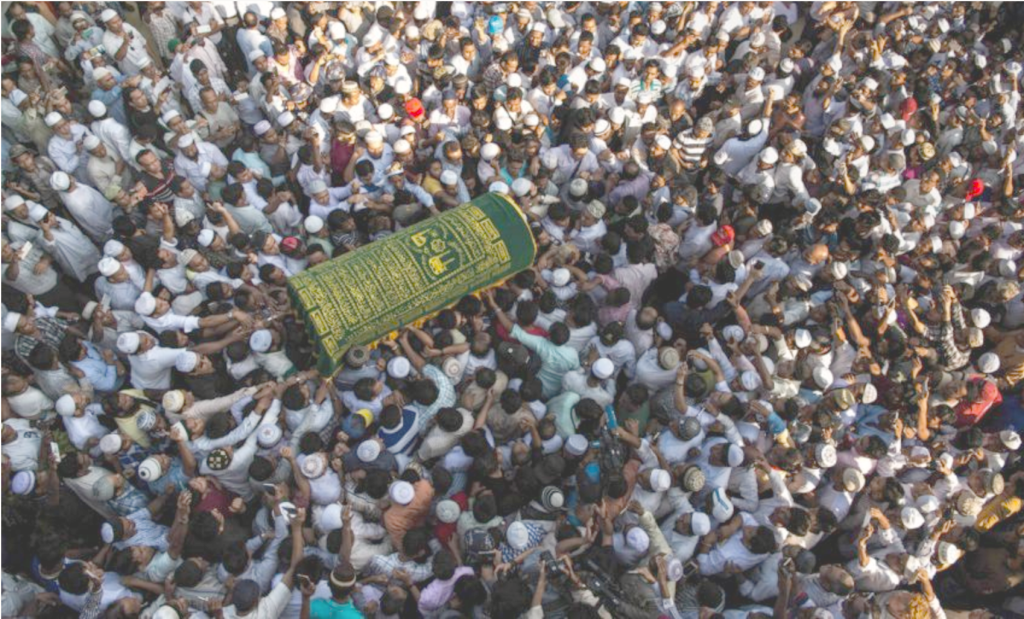

It is a that stage that, all of a sudden, the bad relations between the very large and assertive Buddist majority of Burma and the Muslim Rahingya minority have become an issue of international interest. Disturbances have started occurring in the Rahingya-populated area of Myanmar, where the flames of hatred are being strongly fanned by a yet unknon hand. Most serious, and most criminal, on January 29th, 2017 has been the assassination of a very prominent Rohngya lawyer, Ko Ni, one of Aung San Suu Kyi closest and most influencial advisers, in her effort to combat religeous and ethnic hatred, and strengthen Myanmar’s national unity, against the separatists ideas that are being spread for the creation of a Rohingya independent entity.

Mourners at the Muslim cemetery in Rangoon carry the coffin of Ko Ni.

Such an entity, BTW, happens to be planned in such a way as to encompass the entire coast of Northern Burma, thus casting doubts about the feasibility of other any more ambitious Sino-Burmese projects, such as a railway line from the very important (and beautiful) Chinese city of Kunming to the Indian Ocean. And with disturbances have come news about atrocities and a wave of displaced persons, refugees such as the ones stranded on Nauro and Manus.

“Humanitarian concerns” for them that had even been at the origin of a US-Australian agreement to resettle a few hundred Rahingya in America. Moreover, some media have already started raising the issue of an independent state for the Rahingya, a new independent small country whose territory would – what a strange coincidence ! – exactly encompass the coastal area of Myanmar of greatest commercial interest to China,

Needless to say, the very “politically correct” Western press press has thrived on the existence of this new political and humanitarian crisis: the Rahingya crisis; that is, a crisis that involves a community that inhabits the very costal area that is crucial to sino-burmese cooperation. All of a sudden, very moving articles had appeared in the media about the plight of the Rahingya and about how “the international community has a moral imperative to support them”, and how ”the persistent repression and lack of representation suffered by the Rohingya gives them a right in their own state”. Even Forbes has encouraged its western readership to “Sanction Myanmar And Give The Rohingya A State Of Their Own”, but has deemed a detail not worth of being mentioned the fact that the Rahingya live in a coastal area of outmost geo-political relevance. Which means that, once this new Nation having been created, the US would have the “moral obligation” of protecting it from “sanctioned” Myanmar with a permanent military deployment.

Recently converted to geo-political affairs, President Trump was obviously unaware of this background story. And couldn’t appreciate the political meaning and value to US diplomacy of taking 1,250 Muslims Rahingya on US soil. By once he had probably been informed, and had understood that Obama’s “dumb deal” was not that dumb after all, in the anti-Chinese perspetive of the “pivot” to Asia. How could he, in spite of his anti-refugee furor, remain “insensitive to the plight” of the Rahingya stranded in Nauru and Manus, and to the larger and more general “moral obligation” of giving them a country of their own? It is unthinkable that he could miss the opportunity of manufacturing international consensus for the creation on the Myanmar coast of a permanently conflictual situation that might inflict and extremely serious blow to China’s growth, and become a very serious irritant for the very country the new US President has spotted as the present, main enemy of America.

Leave a Reply