Brexit one month later

Churchill had said: “If Britain must choose between Europe and the open sea, she must always choose the open sea”.

In a summer of discontent, the British have instead refused both, Europe and the open sea.

R. d’Aco – One month after the referendum, British political circles and public opinion seem to have finally overcome the shock of its unexpected results. They have now to face its political consequences. Do you think it is possible to make an objective assessment of the task ahead?

G. Sacco – The emotion with which the result has been greeted, firstly in the United Kingdom, is certainly an event in itself, and the disarray and confusion that have followed are certainly worth being analysed. Even more so are the shouting and vehemence that have characterised the whole campaign. One could indeed ask what has happened to British sang-froid. Where is the capacity to keep a stiff upper lip, probably the main quality that the Europeans – most of all the Italians and the Germans – have real reason to envy? And what has happened to the lessons of Shakespeare? Faced with all this uproar, all this alarums that the EU, and even the post-communist world order is going to collapse it occurs to me to say, like Macbeth: “It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

Well, I do not think that this first impression would be justified. Even if the emotional impact has been inflated by the media, it is in part due to the perception that the majority that has voted “leave” was in reality rejecting not only London’s unconvinced presence in the Brussels institutions, but the much larger phenomenon that is blurring borders and weakening all identities: local, national, and even the initial core of a “European” identity that has hitherto been created, i.e. they were rejecting globalisation. As the Financial Times has written, “Brussels was tarred as the author of globalisation, migration and economic marginalization. In a way, contrary to what Churchill had said back in 1953 – “If Britain must choose between Europe and the open sea, she must always choose the open sea” – the inhabitants of those islands were refusing at the same time both, Europe and the open sea. And, possibly, rejecting globalisation even more strongly than remaining in the EU.

R. d’Aco – An outburst of “little Englander” feelings? Is this that you see you consider as the real surprising event? And how does this explain the sound and the fury of the media?

G. Sacco – Exactly. There has been a clearly political choice to dramatise, and to present as specifically anti-European, the results of the referendum. But, so much frenzy not withstanding, the decision to part company with Brussels seems to me to be, in the end, a matter of modest importance, compared to lack of ideas, the paucity, and the lack of interest for the UK national interest shown by the political class in the first two weeks after the vote.

As US State Secretary Kerry they had no idea of what to do next (and even added that he had a few ideas how to reverse or limit the impact of the vote). For several days it was indeed not even certain that the government in London would seriously go through with the complex procedure and formalities necessary to bring about the exit. Only 24 hours after the results of the referendum were known, Cameron had already said that the launch of the divorce procedure could wait until October, after the choice of his successor. Wait for 4 months! And even the leaders of the ‘leave’ campaign have sought to put things off until a still later and more uncertain date, may be even after a new round of negotiations with Brussels.

One could of course imagine that they have already started squabbling among themselves over who should be installed in no. 10 Downing Street. But, at a closer look, they seem to have been playing musical chairs because none of them wants to be there when the official request to leave will have to be signed. The British have indeed understood – ex post, unfortunately for them – that they have shot themselves in the foot. And if Cameron successor – or successors – will not be able to extricate the UK political class from this trap of their own making, the price will be the end of any political career for whoever signes the application for article 50.

R. d’Aco – But less then three weeks after the vote they seemed to have already recovered their spirits, and to have managed to have a full functioning government.

G. Sacco – Yes. This state of affairs has actually lasted for just about two weeks, when the English establishment has been in a condition of shock and awe for what had happened, and was just trying to “gain” time by postponing the moment in which the inevitable consequences had to happen.

The confusion was evident. Not knowing which way to go everybody was discussing procedure. Cameron had set for next October his replacement by a new PM. More then three million people were cultivating the illusion of a new referendum that would undo what the previous one had done. The Conservative Party was preparing to have its 150.000 cardholding members vote for a new leader among the five declared candidates (a sort of Primary, as murky and ridden as the US ones), and then for the winner to go to the Commons to discuss with the MPs, whom were supposed to be in majority pro-“remain” if and when to draw a conclusion from the “purely consultative” referendum that had taken place. The very leaders of the “leave” movement were saying that formally applying for article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty could wait indefinitely and were each of them trying to make a pause in order not to be signing the formal application. And, for one time in the unison, both the “public” and the “published” opinion were looking towards the Continent in the illusion of seeing everything collapse, because of the UK menacing no longer to provide their precious contribution to ruling the European masses.

Then – around July 8th, probably in the night between the 7th and the 8th – there was a radical turn in the direction the wind was blowing, and a frantic sequence of events was set in motion. Rules and procedure, that had hitherto seemed of the outmost importance, were thrown into the dustbin. The date set to have a new PM was moved from sometime in October to September 9th, and the candidates to the job started to withdraw or fall off one after the other, until there was only one left. The so-called “1922 back-benchers” favoured this clean up of the scene by giving up their long established right to propose an alternative one. And the date for a new tenant to move into number 10 Downing Street was changed again: to July 13 this time.

R. d’Aco – Something had happened …….

G. Sacco – Something had happened, for sure. But what? Strangely, there is no explanation, neither official, nor whispered. Even more strangely, nobody even poses the question. Events have started running at full speed, but one cannot avoid having the feeling that a lid has been imposed to the sound and the fury that have prevailed in the two weeks immediately following June 23rd, and that a stifling taboo surrounds the cause of this sudden change.

It looks as if somebody, somewhere, in some “hard core” of the Kingdom has become conscious of the fact that “gaining time” actually meant “wasting” time at an extremely dangerous moment. That it was bringing about the opposite of what every Briton was expecting; that the world, and the EU with it, would collapse. Well, the world was not collapsing. Neither was the EU, and a majority of people in the EU – namely in those Northern European countries that were considered most sympathetic with Britain – answered “No” to a poll asking whether Europe should give Britain a “rebate” in the cost of moving out.

Actually, as for two weeks nobody in Britain seemed to have an idea of how to proceed, something else had come very clearly in sight: the collapse of the Kingdom. The hypotheses of a Scottish secession, of an Irish unification, and of even Gibraltar going its own way, had all of a sudden become quite realistic, as realistic as the hypothesis that Great Britain could soon be not that great – or at least not territorially as large – any longer. A hypothesis that made the “hard core” of the Kingdom react, in a manner that has proved to be as discreet as it is fast and efficient, for its self-preservation.

R. d’Aco -Nobody seems however to have noticed anything unusual.

G. Sacco – Well! Plenty of other things have happened at the same time. West of the Atlantic there was the final Sanders’ betrayal of the “revolution” and of the young people he has used and exploited to the very end. (How many of them, one might ask, who probably were at their first experience with political engagement, will forever be disillusioned with politics and democracy?). And, as regards the far East, attention was on a dangerously precedent-setting ruling about South China Sea by an obscure tribunal created in 1899 by Nicholas II, the Czar of all the Russias. And in Dallas, something dramatic was taking place, which could mean that racial confrontation has reached, in the US, a dangerous turning point.

But if mass public could have this excuse for their distraction, professional observers of political events cannot hide behind them. None of these events is as meaningful, as “pure” and as fully representative of the political and institutional system in which it takes place, as this most recent performance of the “hard core” of the British monarchic State. By comparison the so-called America’s “deep state”, so frequently mentioned and accused by American “liberals”, looks like a little sect of second-level bureaucrats, self appointed to represent and guarantee the “national identity”, but totally out of tune with the majority of the country. In Britain, with its unwritten Constitution, there clearly is, when a storm is coming, something of much higher grade, which offers the possibly of a last resort.

R. d’Aco – In short, the British lion is back and roaring again!

G. Sacco – This is a little too much; the age of Empire has past. Today, the UK is a middle-size advanced country with a great foreign policy tradition. In this very field, however, on June 23rd, Britain has inflicted itself a very serious and irreversible blow.

And it is already clear that the British, even if in the ends they managed to get a new PM fairly fast, will from now on only be able to aiming – in their relations with the rest of Europe – at delaying things, and at setting in motion a new shilly-shallying and never ending haggle. In which, while continually putting on the appearance of doing the EU’s founder nations a great favour, they will beg for an agreement that could enable the UK to enjoy the privileges of being in the Union but, obviously, without paying the price of its duties and responsibilities.

Moreover, what other concessions could the UK ask for? In practice it is already exempt from many obligations, more so than any other member. Not only is it not part of the monetary union, but also it is not tied the Schengen Agreement that covers free movement of people. London, which seems unable to acknowledge that more than two centuries ago there was in Europe an event called the French Revolution, refuses to subscribe to the Charter of Human Rights. And in general London has the privilege of being able not to apply some EU legislation in matters of justice and internal affairs. And more, the UK enjoys a substantial rebate on the per inhabitant tariff which Germany, Italy and France contribute to the EU’s budget. What other concessions should the British government obtain in order to be in a position to organise another referendum on ‘leave’ or ‘remain’.

In short, confronted with all this demagogic din, the only serious new development worth attention seems to me that Europe has taken a completely contrary position in telling London to hurry up and launch divorce proceedings, and then go away. This was a sign of unusual dignity and vitality. It is all the more positive in that it came first of all from the six founder members.

R. d’Aco -You seem to have a political explanation of the alarm and bewilderment that has that has leapt through the world’s media right from the outset.

G. Sacco – This bewilderment, and even more so the alarm, can be explained by the fact that the British have been politically incorrect, which means that in the ridiculous world in which we live today their “global-sceptic” vote has taken on an almost sacrilegious dimension. In other words what the British have dared to do plainly represents a revolt by ‘public’ opinion not only against the professional political class but also against ‘published’ opinion, which once again has behaved in a grotesque manner.

What can one say, for example, about the Wall Street Journal that has published an article in which it was even said that the vote in favour of, or against, Britain’s departure from the EU was the most important decision taken by the inhabitants of these islands which lay of the coast Europe since one of their kings detached the country from the Catholic Church. What a pity that in the time lapsed since then and today, the British fought four or five civil wars, had a revolution and a counter revolution, cut off the head of a king, set up a republic, proclaimed Cromwell Lord Protector, created America with their Pilgrims, conquered an empire that covered about one third of the emerged lands, secretly encouraged the French Revolution, promoted full eight coalitions against Napoleon, changed the world with the industrial revolution, bravely fought two wars against Germany…..

One could think that certain parts of the media take their readers for imbeciles and treat them accordingly. And that they really believe they can continue to tell lie after lie. It is enough to note that it was the same media that beat the big drums as loud as they could with the message that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction and even an atomic bomb.

R. d’Aco – In continental Europe as well the reaction of the media has be one of great alarm.

G. Sacco – Absolutely! As a French political scientist, and former Member of the European Parliament, Jean Louis Bourlanges, has pointed out for the case of France, but which is true for the rest of continental Europe as well, “the interpretation of the origins of Brexit and of the nature of the EU crisis is systematically marked by a disproportionate complaisance for British views”. On European and international trade issues, “la machine à s’aveugler”, the mechanism to make ourselves blind, “works at full steam, and Brexit seems to be a fairy tale of the European crisis under whose spell politicians, public intellectuals, hommes des media et hommes de la rue, have chosen to be put to sleep, lulled and mislead.”

R. d’Aco – In short the British vote in favour of leaving the EU had an element of revolt against ’official truths’, all ’official truths’, and the media which took upon the job of carrying them.

G. Sacco – There has certainly been a component of revolt against an establishment that thinks it can continue to legitimise its own power by telling bigger and bigger fibs. And fibs that have become less and less realistic since ‘implemented socialism’ ceased to exist.

For as long as there existed in the world two blocs politically and ideologically opposed there have also existed two opposed ‘realities’. And each of these tried to gain followers in the countries that were militarily dominated by the other superpower. To this end the propaganda of both sides tried to put forward information and analyses which, if not true, at least had some verisimilitude and credibility. For this purpose they stayed near enough, if not to the facts, then at least to the perception the public could have of them directly. But after the disappearance of one of the two politico-military rivals, the winning side has since had the space to put around any unfounded story as a truth which it can make its subjects blindly accept. And I ask you to note that I am not speaking nostalgically about communism; I am a westerner speaking about the virtues of competition, which is a supremely liberal theme.

As everybody knows, Churchill once said that once a war begins the first victim is the truth. But in recent years the opposite has happened. With the end of the ‘Cold War’ a climate of general conformity was created, a climate that has given birth to a sort of politically correct idiom which it is forbidden and dangerous not to respect. The victorious West has produced a ‘westspeak’ that – think for instance of Tony Blair speaking after the Chalcot Report – can be worse than the Orwellian ‘newspeak’.

Let us leave to one side for a moment the ‘truth’ which is too big a word and talk of a decent and credible system of information. It has always been accepted that such a system is an essential precondition for a liberal society open to ideas. But now, in the world of globalised information which has been transformed into a power structure, we see that if there is not a clash of diverse ideologies in every field, and of socio/political systems based on these ideologies, then the generation of ideas and competition between them risks becoming diminished and individual creativity and every individual thought run the risk of being flattened out and anaesthetised.

R. d’Aco – The last issue of the ”Economist” makes similar point. It seems indeed to share your view when it says that “today’s crisis in liberalism — in the free-market, British sense — was born in 1989, out of the ashes of the Soviet Union”. Read here! It sees the ‘leave’ victory as “a warning to the liberal international order”, and that – unless people believe what “The Economist” itself tries to convince them of , i.e. “unless that the global order works to their benefit, Brexit risks becoming just the start of an unravelling of globalisation and the prosperity it has created.”

G. Sacco – I have read that article; and have found at the same time extremely clear sighted and utterly pathetic. It indeed admits as a fact that is by now beyond doubt that at the origin of the vote to reject the EU there is “anger at immigration, globalisation, social liberalism and even feminism” (i.e. some of the basic points of the “westspeak”), but then tryes to stage a defence by using all the panoply of going rate in political correctness.

If you read further, you can also read that “In the ensuing quarter-century [after the collapse of European Communism] the majority has prospered, but plenty of voters feel as if they have been left behind”. What a pity that this admission comes a little too late! Unfortunately, after Britain has inflicted herself an irreversible blow. And is also too little, because it says the reverse of the truth: only a few, very few, have prospered in the West, and the majority, the vast majority, have been falling behind.

You can say that a majority has prospered because of globalisation only if you start telling the story not since 1989, but more exactly since January 1st 1979, i.e. if you tell the story of the 35 years since Communist China opened up its labour market to capitalism, and was that very same day recognised by Washington as the one and only China.

R. d’Aco – Do you mean that the “Economist” is cheating, because its assertion that, under globalisation, a majority has prospered can only be considered accurate if one includes the hundreds of millions that have emerged from utter poverty thanks to a peculiar form of Communism; Communism with Chinese characteristics….

G. Sacco – Exactly. Let’s say that the Economist disproves the common wisdom according to which math is not an opinion. But the Economist doesn’t stop there in its explanation of why large numbers of people – in the West – are enraged. The collapse of communism – it writes – “was liberalism’s greatest triumph, but it also engendered a narrow, technocratic politics obsessed by process. Their anger is justified. Proponents of globalisation, including [The Economist], must acknowledge that technocrats have made mistakes and ordinary people paid the price”.

R. d’Aco -The technocrats !? Which technocrats? “Technocratic politics obsessed by process” !? Which politics? Which process? What does this mean?

G. Sacco – Don’t rush things. The most funny bit has still to come!

R. d’Aco – The most funny?

G. Sacco – Yes, funny! Because the Economist goes on: “Elaborate financial instruments bamboozled regulators, crashed the world economy and ended up with taxpayer-funded bail-outs of banks, and later on, budget cuts.” Wow: what an assessment of 35 years of globalisation! And if this is the outcome, the fault is not with the system, but with the bureaucrats! It is not the system that is flawed, but the bureaucrats that are “obsessed by process” ! This reminds me of the language one had to become familiar with when studying Stalin’s Russia. When some catastrophe had to be explained, and a trial had to be mounted in order to put in front of a firing squad some communist Stalin considered a danger to his personal absolute power, it obviously never was the fault with the directives from the centre, never with the ideology or with the system. It was always the fact that the chosen scapegoat had been skhematicheskiy in his implementation of the ideology.

R. d’Aco – But this is not funny at all! This means that “market fundamentalism” is on the way to become “market Stalinism”, as James Galbraith, an eminent American economist, uses to say.

G. Sacco – . I haven’t said that! So, please, don’t attribute to me conclusions I haven’t drawn! And, by the way, I agree on the fact that “market Stalinism” is not funny at all. What I just wanted to to make is an ironic point: how funny the Economist becomes in the next sentence, where it tells its unfortunate readers that the “technocratic scheme par excellence”, …. which “led to stagnation and unemployment” to the point that the normally wise people of the UK went crazy and voted ‘leave’ was (please, type that in Italics)….. “the move to a flawed European currency”! Incredible! So, it is the fault with the Euro, to which the UK was not part, if the British were the first European people to revolt against the establishment! These anonymous authors – that actually are collective authors – really take us for idiots!

What logic is there in this reasoning? This is totally ridiculous! How could it be that the political hegemony of UK’s ruling class is cracking because of the impact of the Euro, which the British have had nothing to do with, while countries like Italy or France – that are on the forefront of the struggle to make the Common currency a tool for deepening the unity of Europe – have shown much more political resilience?

These people at the Economist are really clutching at straws in their denial of the real reasons of the fury of the majority of the English population. And they are obsessed with the Euro, possibly because its success as an international and reserve currency has given a final blow to the British pound. They try to give the Euro the role of whipping boy. In their mind, it has taken the same position of the French 18th century philosophes in the nightmares of all the reactionaries in the following two hundred years. You know:

Je suis tombé par terre, c’est la faute à Voltaire

Le nez dans le ruisseau, c’est la faute à Rousseau.

Si je ne suis pas notaire, c’est la faute à Voltaire

Et si j’ai un petit oiseau, c’est la faute à Rousseau.

R. d’Aco – So, in your opinion, the vote in the United Kingdom in favour of leaving the EU demonstrates is first of all a revolt against the endlessly repeated commonplaces, not to say the lies, with which the western ruling class, in this case in Britain, seeks to hide the failure of the neoliberal model that has been put into practice over the last 35 years and the general impoverishment of the people that this has brought about, be it in Britain or the USA ?.

G. Sacco – It must be said that the side favouring ‘leave’ also conducted a campaign that included sheer falsifications. As a leading legal academic from a British university has put it, “Leave conducted one of the most dishonest campaigns this country has ever seen… On virtually every major issue that was raised in this referendum debate Leave‘s arguments consisted at best of misrepresentation and at worst of outright deception”. And a well-informed and acute British observer, whom I can only quote anonymously, went as far as to say that the arguments of the anti-EU camp would have made Dr. Goebbels envious.

The untruths of the other side, the pro-Europe camp, were simply the sum of all the accumulated commonplaces of the last 50 years of western “published opinion”; the stuff that a few years ago was called ‘the only way’, la pensée unique. The hegemony of commonplaces, l’hégemonie des lieux-communs, was a corrupting and noxious collection of rehashed slogans aimed at steam rolling any individual opinion and at obliterating the hopes of any citizen of being able in any way to influence his own destiny and that of his country. As the French would say, “le communisme a perdu, mais le lieux-communisme a gagné”,

R. d’Aco – At the root of Brexit vote you therefore see mainly frustration, a sense of powerlessness and general exasperation among the British public.

G. Sacco – After the Brexit vote, many observers have – ex-post facto – written that large numbers of people are enraged. Others have said that they are exasperated, which is probably a different feeling, and translates into a different request – less precise than the one we have in classical class struggle – to those who have been ruling in Western societies. The vote to leave the EU undoubtedly is part of a negative psychological scenario of failure and impotence, which is common to the whole of the West, and has been brought on by 35 years of globalisation. We cannot, indeed, postpone any longer the acknowledgement that this has had disastrous social consequences in the western world. On one hand, it has given birth to a “wealth and power super-elite”, the members of which no longer have any connection with their countries of origin.

“National capitalism” that Lenin believed had, with imperialism, reached its highest point, and that was at the origin of WWI, no longer exists. Instead there is a global capitalism that has hollowed out the role and meaning of Nations and of Westphalian States. First and foremost, it is driving western peoples as a whole into a situation of extreme and growing economic restraint; most of all, in a situation without any prospects for a future betterment.

R. d’Aco -You seem to hold a negative opinion of globalisation

G. Sacco – No! Not at all! Globalization has been a positive and powerful phenomenon of rationalization of the world economy. Plenty of manpower resources that were largely underutilized have been brought into productive activities, thanks to a freer and more efficient distribution among countries and continents of capital invested in manufacturing. And great civilisations that for centuries had seemed to be in an irreversible decay have found a way to rebound economically, and re-emerge as great contributors to world culture and techno-scientific progress.

China is the most obvious case of a nation that after a long struggle against colonialism aimed at recovering her dignity and sovereignty, has also re-acquired a decent economic status thanks to globalisation. And it profited most of this phenomenon because it had the world largest supply of high-quality, hard-working manpower, and because its government made the right choices at the right moment. But the Chinese are not the only ones that have profited from globalization, together with the population of other cheap-labour countries which have also attracted a number of investments. Developed countries as well have drawn a positive result from this phenomenon. Western consumers have namely profited from the fact that, for about thirty years, growth has been accompanied by very low inflation. Actually we have seen the phenomenon of new products, mostly in the electronics sector, coming to market and rapidly becoming available at lower and lower prices.

However, as it frequently happens, there have also been negative aspects of globalisation. Growth and development are, by their own nature, unbalanced phenomena, and phenomena that systematically create new social and economic disequilibria. By moving the great majority of manufacturing activities away from Western countries, towards low-wages ones, investors have been able to save substantially on labour costs, so that – after about a third of a century of unbridled movement across borders – about 10% of the world gross product turned out to have shifted from wages to profits.

The country that has suffered most is the United States, whose foreign trade, before the onset of globalization presented a strange feature known as the Leontieff paradox. As a country where capital was abundant and therefore relatively cheap, while manpower was expensive and relatively scarce, the US should have naturally specialized in technically complex products requiring costly machinery, but with little labour content. However, for reasons that have been later explained by another economist by the name of Raymond Vernon, the U.S., before globalisation, had become specialized in new, very innovative goods whose production demanded a big amount of skilled manpower.

This irrationality was eliminated by the process of globalization. So that the Leontieff Paradox is now solved. But the skilled workers that were at its origin have become a crowd of unemployed – and unemployable – middle-aged white men, whose families have become too poor to buy even the products whose price has been pushed down by the move of production to China, are over-indebted to the point that they frequently have lost their homes, and have eventually obliged the Obama Administration to rush to the help of the banking system itself. And when they don’t become alcoholics, or don’t join the huge crowd of the homeless, these once proud members of the US middle class obviously look back in anger at what their standard of living and their expectations were back in the sixties and seventies. And vote for Donald Trump.

This does not mean that globalisation is over, and that we could go back to protectionism. It only means that from now on investment across borders will have to take place in a more regulated international environment. Instead of entrusting such a gigantic and worldwide phenomenon to the sheer action of the spontaneous forces of the market, it should be accompanied by a recovery of their role by nation states. And that new (probably supranational) institutions and new forms of government intervention have to be invented in order to correct the negative aspects that globalisation produces in the short run, and tend to obscure the undeniable long-run benefits.

As it has been said by Emanuel Yi Pastreich – an American social scientist who lives in South Korea, and therefore has a view of globalisation from the other side, the side of those ho have hitherto been the winners -, “Globalization is far from dead. It is morphing into a far more vicious and invisible, creature. …. the whole matter [seems to me] a question of ideological decay. The ideology, values and aesthetics that underlay this global system are decaying. Brexit may not work as planned, but the previous stage of globalization is over.”

R. d’Aco – But what about technological progress? How can one consider that we live in an age of decay, given that science and technology are progressing at a pace never seen, nor imagined, before?

G. Sacco – The expansion of human scientific knowledge is without any doubt the most promising and exciting feature of our time. Its most impressive feature is that, while all other factors of change always had, and keep – at least potentially – an ondulatory trend, with ups and downs, science and technology are on a clearly exponential trend. This certainly poses some worrisome questions, and some people are frightened by it. But, let’s be fair! At least some of the problems that this phenomenon, and even more so the progress of technologies, seem to be creating are only due to the conservative reluctance of societies, when confronted with the need to adapt, or to the illusion that adaptation can be easy and not painful.

Take for instance the so-called American dream. Many still pay verbal homage to it. But the underlying notion, the notion that through hard work one could change social class, is completely dead. And its place has been taken by the prospect that unless you are one of the very few who, after a lucky strike, succeed while young in becoming billionaires, you will end up among the thousands of homeless, alcoholic and often on drugs, who roam the streets of big American cities like aimless, disorientated herds. California, in particular, the land of the ‘gold-rush’, is today full of young people first lured and fast disappointed by the myth of the ‘start-up’, that end up as human trash, or nourish the phenomenon of the “silicon valley suicides”.

This has various consequences some of which, and by no means the most dramatic, are the sense of loss of identity, the rage against the establishment which has taken America by surprise with the Trump phenomenon, and the apparently incomprehensible exasperation of the masses which for months has convulsed France. The Brexit referendum has revealed a groundswell that more than just rejecting Europe, wanted to ‘bring down everything’, just as when, in August 2011, a fearsome mob sacked and looted shops in many areas of London and eventually penetrated as far as Oxford Circus, the heart of London’s shopping nexus thus sending shivers through the establishment. But, interestingly enough, not all shops were looted; this was a modern mob, streetwise and discerning, looting with intent amid the sacking and destruction. Its main targets were electronic goods and leading brand names in clothes, footwear and accessories; some participants were even spotted trying on shoes and clothes for size.

Foodshops were also targeted, but I don’t think these disturbances can be deemed real “food riots”. I do not think it was really mainly a matter of hunger, except maybe when they became hungry during their looting exertions. There certainly were among them some seriously poor and homeless people. But by and large the rioters, more then hungry people, were people exasperated by the growing burden downloaded on the individual by our contemporary life style, in which complex “do it yourself” operations become more and more frequent in order to access to elementary public services. Interestingly enough no one thought of smashing the windows of bookshops and stealing the contents. Probably, they had no use for words or theories; they no doubt felt they’d heard enough already.

R. d’Aco – The London disturbances of 2011 took everyone by surprise. Such phenomena occur regularly in France, but are not usual in England. And the reasons behind them have never been analysed in depth or truly explained.

G. Sacco – This is true. On both sides of the Channel this rage and exasperation offer an unusual analogy today. And, in the last analysis, people are, paradoxically, in revolt against the European dream. And this is all the more tragic, because for half a century the European dream has been the Old Continent’s true political superiority over America which, after the brief reign of Kennedy in the White House, has had no more dreams to offer.

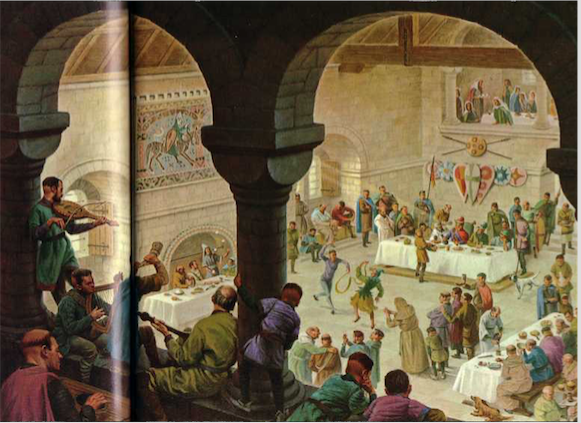

But if the absence of ideals on the continent gives shape to forms like the National Front in France which, when all is said and done, the establishment has until now been able to confine to the margins of power, things are different in the UK where a substantial section of the ruling class has also come out openly against Europe. The explanation lies in the fact that, not withstanding the role of the City of London in globalised finance, and the fact that London has become one of the world’s richest and most expensive cities, the composition of the privileged class that dominates the rest of England is different from the one that prevails in the capital, which voted to remain in the EU and permits itself a globalising ‘snobbery’ such as a Muslim mayor. Outside of London there is in the dominant British class a much older pseudo-aristocratic and squirearchal component which – in social and cultural tradition, if not DNA – goes back to William the Conqueror and the sharing out of the land he had conquered a thousand years ago among the leaders of the Norman clans that followed him.

Q – Do you really mean a privileged class whose lineage goes that much way back? Or you just say that to mean a patrimonial élite, whose wealth goes from generation to generation by inheritance.

G. Sacco – No, no! I mean exactly what I said. And in any case the very members of this feudal class do not hide it any longer, the way they tended to do as long as the fear of communism was there. Not so long ago, the late 6th Duke of Westminster, the third richest billionaire in the UK, said to be worth around 11 billion dollars, and whose estates include swaths in Mayfair and Belgravia, near Buckingham Palace, much of which his family has owned since 1677, was asked by a FT Financial Times reporter what advice he’d give to young entrepreneurs keen to emulate his success. “Make sure they have an ancestor who was a very close friend of William the Conqueror,” he replied. And Cameron himself, although not that rich, came from this caste.

R. d’Aco – So Cameron was hammered and defeated by his own class?

G. Sacco – No, of course! His social class is not numerous enough to have a deciding weight in a referendum. Cameron was hit and sunk by the vote of the millions of those excluded from the mainstream of life, who have seen their situation worsen during the last 35 years. The pseudo aristocratic class merely added to the votes. As everyone has stressed, Cameron ended up defeated by his own mistakes, because he is a very mediocre politician and strategist. And it is in this, in his being at 10 Downing Street while being a mediocre, that the responsibility of his class of origin can be seen.

In a country like England where the profound shadow of the class system still underlies much of the social structure and mainstream politics it is not necessarily the most suitable candidates who emerge in positions of power and responsibility. Cameron is the fruit of this contrary selection. It can’t therefore be a surprise that he risks going down in history as the Prime Minister who detached London from Europe and, if Scotland decides instead to remain, as the politician who absolutely destroyed the United Kingdom.

R. d’Aco – Isn’t it a little unfair to put on one man all the blame for such a totally unhappy ending?

G. Sacco – Of course, it is unfair! The entire political class is responsible! But he was in charge, and the judgements of history are seldom fair. In any case, you are right. Brexit, for those who are belatedly enraged, is also the fruit of the obstinacy of a small social group seeking to stay in power whatever the cost, in the same way it has done over the span of nearly a thousand years, except for a few, temporary knocks.

A thousand years is an enormous amount of time, for sure. Yet England – from the social perspective – has remained one of the most static countries. This is well illustrated in Jane Austen’s novels where the characters fall in love and marry among cousins in order not to divide up their patrimony. This was 200 years ago, but a recent OCSE study has shown that today, too, in the UK just short of ninety percent of the population occupy a social position on the same level as that of their parents. In France, on the contrary, this figure is 31%.

Unlike America where the privileged class is more and more made up of the nouveaux riches who made their fortunes in the technological field and above all in speculative finance, in England where there has been no Silicon Valley phenomenon, the ruling class is composed not just of the City of London environment but also of a class of country gentry which the reform of the rotten boroughs in 1832 did not succeed in destroying, whatever the official version. It was rather a class with which Charles Grey, Second Earl Grey, the Whig Prime Minister from 1830 and promoter of the Great reform Act of 1832 (and of the abolition of slavery one year later) had to compromise.

This composite aristocracy of land and money does not, unlike American billionaires, incline towards the accumulation of ever bigger fortunes to be shut away in Swiss safes or fiscal paradises. To be sure! Not even they are immune from the universal feelings of greed that dominate the contemporary world, the most loud and vulgar examples of which are the Russian oligarchs who, not by chance, see England as their promised land. But the British ruling classes feel above all that their privileged position is legitimised by a tradition of political and social dominance that goes back to medieval times and which gives it the legitimate right to a ruling role , both in their eyes and in the eyes of many of Her Majesty’s subjects. Thus their intention is to remain at the helm of the country even independently and against the general economic interest of the UK. They have always been in command and want to continue to be in command. Their aim is purely the retention of power. In this, their aim is very different from the wild accumulation of wealth that characterises the class that has been born by, and has grown up with, globalisation. And this meant that they worked and voted for ‘leave’ despite the fact that Great Britain has largely profited from and would have continued to profit from being in Europe.

R. d’Aco – Britain’s class structure – the way you describe it – seems not only more ancient and resilient, but also way more complex than the US one.

G. Sacco – English social distinctions, classes, way of life etc is an extremely complex subject…. And on the surface there are changes as well.

I could easily myself object that what I have just said on schools and entry into top public service jobs etc., actually is no longer totally true. Entry into leading public service jobs is by exam, and entry into leading schools, such as Eton, is also in many cases by exam. And, by the way, you can see the first signs of selection by merit, (as well as by money) in the fact that there is a growing number of Chinese students in some very exclusive institutions.

R. d’Aco – Why? Are the Chinese better than others?

G. Sacco – No, of course. All human beings are equal. But since time immemorial the Chinese aristocracy has seen culture as the tool for preserving social privilege, and – conversely – in revolutionary China, education has become the main way for upward social mobility. It is however of some interest to note that the moment when Chinese students landed at Western Universities on extreme merit passed two decades ago. More recently, the contact with western “values” has subtantially changed things. Indeed, as it has been pointed out by the same academic you quoted before, James Garbraith, who is a scholar of these specific issue – inequality –, such “inculturation” has made that the Chinese now coming to Eton are more and more from the newly-rich strata of Chinese society (as they are at places like Harvard, where they are accepted for cash) and very seldom, if at all, chosen by merit.

It might indeed be worth noting that the new leader of the post-Brexit Conservative Party, Theresa May is state school educated. And none of the recent Conservative Party leaders before Cameron (Thatcher, Major, Hague, Duncan Smith, Howard) were “public” – which, in Britain’s English. means “private” – school boys (or girl), ie they had free education and were not from rich or ‘upper class’ families. The internet also has made access to valuable information tremendously easier. And these recent changes have probably added to the fury of the traditional ruling class towards Europe seen as a threat to their position, and towards globalisation.

But this dos not mean that family social standing does not play a part any longer. It still does, but maybe in not such an overt and overwhelming fashion. And money also plays a large part, and there are Russians at some of the most expensive schools. You know, Britain is very welcoming to a certain type of Russian emigré familiy …

In any case, the shadow of tradition, such as I have tried to briefly describe, is a long one and still permeates the English social and professional consciousness. A person’s background may weigh heavily in some professions, such as the legal professions. And if wearing an Oxford or Cambridge college tie is probably no longer sufficient to guarantee that you end up on the winning side in case of a dispute, a person’s speech ad accent can immediately label them as “us” or “not us”.

R. d’Aco – So if you had been English you would have voted to stay?

G. Sacco – It would have depended on my social class! If I had been a university Professor, a pensioner, a person who can rely on the public health system probably yes; my most mean and immediate interest would have been to vote ‘remain’. Membership of the EU puts a limit of sorts upon the animal instincts of globalised capitalism even in the UK . If instead I had been a former worker of the Sheffield steelworks, like the protagonists in the ‘Full Monty’ , in short, if I had been someone who had nothing else to lose perhaps I too would have lent a hand to bringing down everything.

In this connection I would like to make the observation that on the night when the votes were counted it was the big success of the ‘leave’ vote in Sunderland, at the best a practically unknown town in north-east England, that brought about the collapse of the pound sterling on the markets of East Asia that were already open. And why? Because in the past Sunderland had been an industrial town with important ship-yards now closed having been driven from the market by South Korean competition. And today it is an especially and terribly depressed area, near enough to the Sheffield of the ‘Full Monty’. And the stock market operators and currency speculators understood from the way the vote in Sunderland went that the most humiliated and ignored stratum of British society was in revolt; they guessed what the result of the referendum would be and began to sell sterling.

R. d’Aco – But isn’t it a bit senseless to vote against Europe, to rebel against the Brussels bureaucrats as a protest that Korean competition has eliminated so many jobs?

G. Sacco – It seems senseless but in reality it is less so than one might think. Certainly the jobs in the Sunderland shipyards were destroyed a good many years ago, long before –something that these unlucky people probably don’t know – a few months ago the EU’s bureaucrats signed a new bilateral free trade treaty with South Korea against which even Fiat-Chrysler CEO Sergio Marchionne’s objections were powerless. They were protesting against the opening of borders to international trade generally which they see symbolised in the UK’s membership of the EU. And in essence they are not that wrong because the Brussels bureaucracy is now so rigidly the creature of the neo-liberal ideology propagated – and the disgusting Barroso case shows by which means – by the 10,000 lobbyists from big global companies that are in Brussels that they will sign without thinking twice any piece of paper put on the table provided it contains the words ‘free trade’.

Also voting against Europe as a protest against immigration – the other element which explains the vote of social classes like those of Sunderland – is less irrational than one might think if one notes that the majority of immigrants in the UK come from the Third world rather than Europe. However, in the eyes of this now unemployed working class, European immigration seems more dangerous when it comes to competition for jobs.

After the 2005 terrorist attacks and in order to allow for a wave of anti-Islamic feeling among the public, the government in London was in fact in favour of immigration from the eight new EU member states of central Europe that had been admitted into the EU en bloc the previous year as the finishing touch to the reign of the European Commission’s President Prodi. The four million potential immigrants that it was calculated there were in these new member countries and who did not have the legal right to move into the countries of the Schengen agreement, seemed, in the eyes of Downing Street, less dangerous and more easy to integrate as they were very different from immigrants coming from the Third World. They came mostly from Poland, Romania and the Baltic countries which meant they were white and not Muslims and had an excellent technical education, which the communist countries had always promoted. But it was just these factors that made them suddenly appear, and still appear, as especially dangerous competition to a British working class which found itself ever more on the fringes of mass unemployment.

R. d’Aco – So in a certain sense you understand, if you do not truly justify, the reasons for which the most disadvantaged classes of English society voted ‘leave’.

G. Sacco – If you insist on asking me how I would have voted if I had been a British subject I must tell you that, as a university professor who happens to be decently informed, I would have taken into account the general interest of my country and voted ‘remain’. But I would not be completely honest if I did not tell you if I had been one of the unfortunate, uninformed, disperate former shipyard workers in Sunderland I would probably have voted the way they did.,

But I ask you to believe that it is almost impossible for me to reply to you question; I cannot imagine myself either as culturally English or as a subject of a queen who claims to be the spiritual leader of a Christian church. Being a citizen of a secular Republic like Italy, founded upon the will of the people, is too strong a part of my personality to enable me to imagine otherwise.

R. d’Aco – And as a European?

G. Sacco – As a European – and this is an identity that fits perfectly with my being Italian – I think that Brexit will in general have a positive effect on continental Europe and its institutions. It will probably put an end to the senseless enlargement to new members And might possibly lead to other peoples, such as the Poles, shooting themselves in the foot the way the English have done. This might be a step forward towards a smaller, more coherent Europe.

R. d’Aco – Yet there is great uproar in Brussels where they only speak about the problems which the British departure will cause.

G. Sacco – That is understandable. Brussels is the kingdom of European bureaucracy, and of a bureaucracy that has turned the European dream into a good money making business for those concerned who tend to exclude anyone who does not revolve around the office blocks of the Commission. And there will undoubtedly be some problems for the bureaucracy. Perhaps some of them are alarmed because they have realised – but I would not greatly count on it – that a big part of the main trouble and of the irritation and hostility that the EU arouses comes from this very bureaucracy which is as obtuse as it is arrogant. However, I repeat, if Great Britain really leaves the EU, there will be a problem or two in their cheerless and well paid humdrum routine. And someone will lose a job, something never before seen in an international organisation.

As an example one can take a problem that will affect all the bureaucrats and lobbyists who maintain them, the problem of working languages. In theory all the 24 languages of the EU countries are official languages since, still in theory, all the member countries are equal. But the fictitious nature of this equality can be seen in the fact that there are only three working languages; English, French and German. But this too is a fiction as few of the officials really know German and very few use it as their working language.

Today French and English dominate; French because it had already taken root before the UK entered the European Economic Community and English which became gradually more preponderant in the years following the UK’s entry. Suffice it to say that in recent times new officials have been accepted through a process that provided for the knowledge of at least one or two Community languages, as well as the official’s mother tongue, but British candidates, from whom only the knowledge of English was required, were excepted.

After the British vote and the successive steps necessary to remove the ties between the UK and the EU, somebody has already said that the English language ought in principle to be eliminated as an official language of the Union, because the Irish already have got Gaelic. This is clearly nonsense, and indeed a case is already being advanced that it should be kept as a working language the reason being that 28% of the population of the rest of the EU after British withdrawal have English as a second language. This is a premise that is obviously fictitious but people are pretending to believe it and it will probably end up with more use being made of German in discussion and documents, French retaining its position and English remaining dominant in informal conversations – the ones that, most notably in the lobbies and corridors of Parliaments are frequently the most important – and the first drafts of official documents.

In other words, even if the UK was to totally disappear from the EU, and even – as a single country – from the very map of the world, English as a lingua franca would be an extremely important heritage to a united continental Europe. And would even add that, should in a not too distant future English become the working language of united Europe, this would be of great benefit. The babel of languages inside the EU is not only a source of waste and of misunderstanding, but also of jealousies and rivalries among the members States. Until Britain was there, making English the de facto language of the European institution would have given Britain a position of privilege. Once she will no longer be there, this problem will be solved.

R. d’Aco – You are not going to tell me that Britain’s exit creates no problem to the Brussels institution, except one of languages ….,

G. Sacco – Of course not. Another, and much more serious problem for Brussels is that very many important positions are held by British officials. It will be necessary to substitute them gradually. Many of these will try to take on a putative Irish nationality. Others will seek to become Belgian subjects on the grounds of their long residence there. But there are national quotas that need to be respected and this will be an opportunity for Italy and one Italy should not lose to be less under-represented and badly represented than it is today.

R. d’Aco – And from the point of view of decision making how will the power relationships in the EU be affected?

G. Sacco – The power relationships in an institution like the EU which with the decisive input of the UK has lost all its representative characteristics and become a purely intergovernmental structure are measured not in the European Parliament but rather in the Council particularly in matters of economic policy.

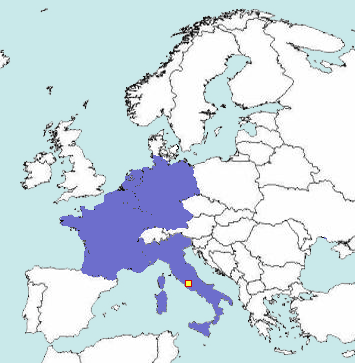

Thus the EU’s real decision making mechanism consists in a permanent trial of strength in which Italy whose representation has had a tradition of weakness, bad reputation and internal division has systematically lost out. Apart from Spain which inherited from the Franco era a centralised, and strongly nationalistic state structure and sells its vote dearly in exchange for finance and special arrangements, there will be two countries that have dominant influence in the post-Brexit EU, France and Germany.

These are two founder member countries who, over a long period, have tried to bring about true reconciliation and create a real and decision making axis. And London has entered into the play of their influence as the ally of one or other of the capitals depending on the circumstances and also in as a balancing factor. Without the English the cooperation-competition dialectic between France and Germany will become more rigid, the axis will become more powerful and a French front for German interests more clearly indispensable. And the influence of Paris inside the axis will perhaps emerge stronger.

It will become more difficult for Germany to use its power of veto in matters of economic direction. As ‘’Le Monde’ has pointed out, according to the voting rules introduced in November 2014, in order for there to be a blocking minority in the Council there must be at least four member countries representing at least 35% of the EU’s total population.

With the UK out of the EU the ‘neo-liberal’ bloc that was made up of the UK, Netherlands and the Czech Republic will lose considerable weight. And Germany, which frequently associated itself with this bloc in order to pass the threshold of 35% necessary for a veto will have great difficulty in its strategy of depriving the EU of authority to the advantage of member states’ governments and thus Berlin.

However the Franco-German axis has serious problems in the immediate future. Hollande is extremely weak and has been totally discredited in France, while Merkel who must face elections next year can no longer count on her socialist allies who have already begun their election campaign. And, most of all, has recently shown – namely when confronted with the immigrant crisis and, later, with the results of the Brexit – there is a seriously worrisome undecidedness.

She is clearly sailing without a chart, playing things by ear, without a political line, with frequent twists of the steering wheel and sudden about turns. In these conditions piloting the rest of the EU consisting of 27 countries all seeking a way of profiting from the retreat sounded by London, will become too difficult for the Paris-Berlin axis. Thus both capitals seem tempted by the idea of associating Italy with their enterprise.

This was visible immediately after the vote. Hollande who, like Merkel too, was convinced that the vote for Brexit would not happen, had already invited himself to visit to Berlin in the following week. But Mrs Merkel, convinced that, with Britain gone, there will be a complicated settling down period, also invited Renzi. At this French diplomacy made haste to set up a dinner for Hollande and Renzi. Thus was born a kind of ‘directorate of three’, which has stuck in the following weeks, and seems to be working efficiently. In short the role and the weight of Italy had already increased in the days immediately after the vote.

R. d’Aco – Two days after the Brexit vote the Italian daily Il Corriere della Sera put on line an interview with Ambassador-turned-political analyst Sergio Romano in which he directly contradicted the political line of the same paper, and of the majority of what you call “the published opinion”, which shows a lot of comprehension for the British political establishment, and for the –probably invented – category of people who voted “leave” by error, and have supposedly repented the very following day. And this independent and fairly outspoken observer explicitly said that Britain had entered the EU ‘so that Europe could not be created’. He also added that London departure was a positive development, because it would now be possible to take up the original project of making a Europe with much more unity and agreement.

G. Sacco – To be sure! And that is also what I would hope for. But it cannot be said that there were no results from the past, that there are no marks. London has been in the European Community and then the Union for forty three years, and in this not negligible period of time has extensively realised its own plan to make any deeper union impossible by opening it up to a huge number of new countries that, having had completely different historical experiences, have nothing in common with the six founder members.

We need to be realistic and take into consideration that in the territory where European unity should be constructed there is the cumbersome heritage of the policy of uncontrolled expansion which was desired principally by Mrs Thatcher just to make impossible any deepening of integration. Thus solidly established in the institutions of the Union are countries like Spain and Portugal that, fortunately for them, have not had the experience of two world wars and total defeat. Above all their history since the end of the 18th century is separate from that of western Europe and tightly bound up with the gradual loss of overseas empires. Their contemporary history is not that of Italy the decisive dates of which – 1797, 1815, 1820, 1830, 1848, 1870, 1914-1918, 1945 – coincide with those of the main stream of European history. And they coincide because the political phenomena that rocked Italy were the same that rocked the whole of Europe. In other words there are in today’s union of Europe countries where developments over the centuries do not match those which brought the six founder members of continental Europe to the historic, unifying decisions of the 50s.

And that is not to mention the Scandinavian countries which have always been hostile to any form of European integration and the peoples, admitted en bloc a few years ago, who had belonged to the Soviet empire and only recently attained a form of state which was, in effect, more or less independent. Before that they were always under the rule of Austria and Germany, or Russia, peoples more than countries whose behaviour in the community institutions has always been all the more haughty and quarrelsome as their national identity has been fragile and uncertain.

In short, Brexit will leave behind a sea of ruins mostly brought about or encouraged by London’s European policy. Europe is today profoundly defaced compared with the one Britain entered forty three years ago, and it will not be easy, even if all the original six members want it – and it is not a given that the new unified Germany still wants this – to reactivate the former project and dream.

R. d’Aco – But is the European dream dead then? And was it in vain, the generous idea to construct, in a world in which the European population is an ever decreasing minority, a new entity which would surmount the egoisms and ambitions of domination of its peoples and really bring them together around the notion of a common heritage?

G. Sacco – No, I do not think the dream is dead. And, if the EU suffers some serious setback in the future it will certainly resurrect itself. There is still the possibility of an armed conflict on European soil, that some transnational forces – and entities that are, strangely, at the same time under and above the power of the State – are trying to find a pretext for. The prospect of such an armed conflict could bring about, as a reaction, something like an anti-war, pan-European and pro-European uprising. At first sight this might seem completely unrealistic. But it is not more unrealistic than ignoring how strongly and deeply the European identity and idea have taken root.

What is evident, however, is that the reality of the world in which the European project was initially conceived and launched, has changed, from an ideological viewpoint as well. Little known to the European public opinion, the Gatt rounds have systematically – since the inception of European unification process – been devoted to arrange negotiations in favour of world liberalization in every field in which the Common Market, and then the EEC, had progressed in the integration of its member countries, in order to dilute the impact of Europe’s unification process. What could indeed mean being member of a club, if non-members can have access to the services and help it provides, more or less at the same conditions of members? This was the aim of the Gatt, which in the end became the WTO, and its impact on the EU became the very impact of globalisation. And while the Gatt was working at reducing the significance of the destruction of the borders inside Europe, Britain (and of London-based lobbying companies) were working from the inside to transform the EU from ideological viewpoint, so that now Brussels’ grey bureaucrats endlessly repeat the same cheap neo-liberal commonplaces.

R. d’Aco – Do you mean that, with the famous Kennedy Round, the American President that the Europeans love most, has been helping to weaken the Union.

G. Sacco – One should pay attention to the dates, before coming to such a conclusion. The Common External Tariff of the European Economic Community was foreseen since the very early stages of the Common Market, but didn’t exist until 1968. By then, Kennedy had already been assassinated. And, by the way, the so-called Kennedy Round (the sixth Round of Gatt negotiations, didn’t start until May 1964, one year after Kennedy’s had died. The name Kennedy Round was invented ex-post, the very last day June 1967, to honour the memory of the President who, in 1962, had launched the Trade Expansion Act.

John Kennedy’s attitude towards European unification has always been far more favourable that that of any other US President. Even de Gaulle, who was himself rather euro-sceptic, mainly because he was very aware of the hostility that the idea of a unified Continental Europe raised in the Anglo-Saxon world, once said in a public speech that the “pendant le court passage de Kennedy à la Maison Blanche”, the unification of Europe could perhaps have been possible.

R. d’Aco – The liberalisation of world trade thus appears as an alternative, even a menace to the unity of Europe. Bur wasn’t European unification always a liberal idea? Didn’t the European project revolve since its inception around a process of trade liberalisation?

G. Sacco – Not really. Originally, when the European institutions were first created, the ideas that today are put forward to justify globalization and explain its roaring success for a good third of a century, were not very popular. And certainly were not the inspiration of Europe’s founding fathers. The Common Market of the six original countries espoused the ideas of laissez faire, and did in fact abolish plenty of laws and regulations that impeded trade among the member countries. But, as a whole, the idea was to protect it with a common external tariff. And before the Common Market, there had been the creation of the Coal and Steel Community, which was a supranational institution entrusted with the task of planning two main strategic sectors of the time. And after the 1956 oil crisis, the creation of Euratom – whose slogan was l’atome unira l’Europe – pursued an objective that was clearly autarchic. Actually, so autarchic that it not only aimed at freeing its Six members of their oil dependence from the Middle East, but even from of their nuclear fuel dependence from the USA. That was indeed the purpose of the Superphenix project, the purpose of enabling the Euratom members to be, as a whole, totally self-sufficient.

At the very origin of the European dream we therefore find three ideas – Planning, Protectionism and Autarchy – that are anathema not only to neo-liberals, but to most of our contemporaries. And the founding fathers had as their purpose the implementation of these ideas in order to create a sort of European federal – or at least confederal – state that would be on a par with the USA and the USSR. This was the opposite of what globalisation has been doing in the last 35 years: weakening the States – all States, not only the ones who were intended to form the Euand transferring their role to a sort of nebula of trans-national de facto powers.

Still, something of the old approach survives still today, in a difficult negotiation presently underway about whether China can be treated as a market economy. Way back in 2001, when she became a WTO member, China was promised to be granted this title in 15 years time, i.e. in 2016. Now that this deadline is approaching, however, the Western countries and most of all the EU have become very reluctant to abandon the transitional arrangement to protect their home market from what they see as the “dumping” of Chinese products. The interest at stakes are enormous. According to calculations made by the European themselves, the EU might lose between 1.7 and 3.5 million jobs. But even if they’re half that much, it is a lot. And China hasn’t got the powerful lobbying and corrupting machine of some big western group, so that, all of a sudden, the protectionist mentality of the fifties has become fashionable again.

R. d’Aco – Are you proposing that Europe goes back to protectionism?

G. Sacco – Of course, not. Going back to protectionism would be impossible today, for a variety of reasons. Some of them are technical reasons; just think of information flows, that have become such an important part of our trade and exchanges. Controlling them would be irrational and almost unfeasible. And just think of the impact of 3D printers, that make it possible to reproduce here and now an object that is available on the other side of the planet, and raise a question I haven’t yet explored enough. Could the copy made by 3D printer – let’s say – in France, of an object moulded by a craftsman in China, be considered an import, be taxed, or banned?

Going back to protectionism, it would be technically rather difficult today. And in any case, no reasonable person would propose such a U-turn. All I’m trying to say is that revolting against European institutions and their activity in order to complain of the results of a very fast process of globalization is a fundamental political mistake; a mistake which could bring about the destruction of Institutions that are actually precious.

The process of European integration should not be seen as the beginning of globalization. They are not the same thing. European integration was basically an attempt at reproducing on a larger scale the states the way we had known them in Europe. The only thing that this new political construction would have missed compared to the old ones, would have been – because of the multicultural composition of its population – the strong feeling of national identity that had become so prominent in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, i.e. in the Romantic age. In other words, the European supra-national system would have mitigated the very factors which, pushed to the extreme, had brought the nation states of Europe to savagely fight one another. And this seems to me an objective that would still be today worthwhile pursuing.

R. d’A. You are practically saying that in a little more than a generation, not only peoples and their leaders have changed, but their very ideas in the fields of politics and economics.

G. Sacco – To understand the difference between then and now, one has, before anything else, to consider the fact that the six original countries that founded the Common Market were the three European nations that had been defeated in World War II, plus some smaller countries. Even France fell into this category, in spite of de Gaulle’s masterpiece of diplomatic and political achievement in having France formally accepted in the group of the victorious nations. By uniting and presenting a new peaceful and cooperative face on the international scene these countries were able to make up for much of the disrepute into which they had fallen and partly reduce the pain and resentment at the wounds they had only very recently inflicted upon one another.

What is more, the nucleus of this new political construction was well balanced for the three principal countries, France, Italy and a hugely crippled and diminished Germany had similar demographic dimensions. Moreover they were three countries which, thanks to the American initiative, had set out to rebuild their own industrial structures in an integrated and complementary fashion rather than as self-sufficient rivals. And let me say, en passant, that for this Europe owes a huge historical debt to the United States, a debt so big that it will never be possible to repay it.

The gift that the Americans have, after WW II, made to European peoples has indeed not consisted of the financial and technological transfers of the Marshall Plan, but of the conditions that were attached to such transfers, namely the conditions for spending this money had to be unanimously decided by the European governments. In fact, they obliged a group of quarrelsome and violent competitors for economic and political supremacy, to take up the habit of day after day compromise and agreement.

Washington’s aim was, obviously, influenced by the American political and strategic interest in having the Western Europeans nation-states prosperous – so that their working classes would be less sensitive to communist propaganda – and at peace with among them, so they could better help confront the Soviet menace. But in the constraint that the Americans forced upon us lies the root that has brought about the reconciliation among the peoples of continental Europe, the reconstruction of their industry along the logic of complementarity rather than the logic of rivalry and autarchy, the Common Market and eventually the European Economic community; a root that has kept nourishing concord and cooperation among the Six original member countries, at least until the moment this small club started being enlarged by, and eventually flooded with countries that did not share the same aims and the same spirit of reconciliation.

R. d’Aco – Are you, in synthesis, saying that Truman’s America created Europe and Britain has tried d to sabotage it?

G. Sacco – This is probably the way in which a populist european politician would put it. But this would be only one side of the picture: the view from the outside. In my words, I would say that at a precise moment in history there was a convergence of external factors that favoured reconciliation and cooperation among three great European nations. All by themselves, these external factors would however, not have sufficed. The push that has been crucial has indeed come from inside these three Nations. Crucial was, above all, the fact that the three founder countries were going through a political phase that was especially favourable to the birth of a united Europe, because all three were ruled by political forces that were in a minority compared to the hard, traditional nationalism that had been historically dominant in all three.

Schuman, the French Prime Minister, had been born in Luxemburg; his father was from Lorraine and had moved away when, after 1870, he found himself a subject of the Kaiser. And in 1919 his son made the same short journey in the opposite direction, after Lorraine had been returned to France. That is, Schuman represented that part of France which had belonged to Germany until the end of the First World War. And which happens to be so Catholic that even today, by a Concordat signed by Napoleon in 1801, some of the principles of the secular state do not apply to Alsace-Moselle. In other words he came from a Catholic political class that had historically been oppressed by both, German militaristic nationalism, and France’s traditional Jacobin extremism.

The Head of the Italian government was De Gasperi, who – after becoming Italian in 1918, as a result of the Austro-Hungarian collapse – had been, in the twenty years before WWII, an open enemy of fascism and of its aggressive imperialism. But he had also always been hostile to the Masonic, post-Risorgimento and nationalistic environment of pre-fascist Italy. As an alumnus of Vienna University, a Habsburg subject, and a deputy representing Trento in the parliament in Vienna, he had been working for a peaceful transfer of the Italian speaking areas of Tyrol in exchange for Italian neutrality in WWI. And he had of course spent years in prison in both Imperial Austria and Fascist Italy.

And, finally, Adenauer was the voice of Rhineland Catholicism, i.e. he was part of a tradition against which Bismarck had fought a harsh and real politico-cultural war, the Kulturkampf. First and foremost, he represented a Germany of which Prussia was no longer part, i.e. an amputed Germany, separated from what had always been the very heart of those militaristic and imperialistic traditions that had dragged the Reich into two tragic wars, both lost, against West Germany’s new European partners.

Of these three men who founded Europe it is said that they could have met without interpreters and could have understood one another using the same language: German. That is absolutely true; but language was not the most important thing these three statesmen had in common. There was much more. Not just the ideological matrix based on Catholicism and strongly pacifist, but also, and above all, their having not been part of the political culture that in each of their countries had greatly fed and stimulated a mutually aggressive nationalism.

Today things have changed profoundly. There are, however, important European institutions, although raped and humiliated by people like Barroso. They exist, and it is from them that a new start must come. Even if they need to be made more politically responsive and less bureaucratic, more efficient and less powerful, less gigantic and all embracing; and, for this, the departure of Britain will be an important step. But this renaissance needs to be done with great prudence and bearing in mind that the exceptionally favourable conjuncture is no longer there; that the political situation of the origins no longer exists. Today, Germany is led by a political figure whose roots are strongly in the east of the country; and that – mostly in the former GDR – there is a resurgence of nationalism and xenophobia, not to put it worse. And Italy itself seems to be losing the enthusiasm with which it has hitherto supported the unification of Europe. From the very beginning, indeed, the Italian perception of the unity of Europe was powerfully influenced by Mazzini’s view, as the continuation of the Italian Risorgimento, the cultural and moral revival that, in the 19th century, had led the political unity and independence of Italy.

Dr. Raffaella d’Aco is a Franco-Spanish scholar of European history and literature.(raffaelladaco@gmail.com)

Prof. Giuseppe Sacco is the founder of The European Journal of International Affairs (g.sacco@yahoo.fr)

Leave a Reply